Colon

The colon smells like poo... 'cause that's where poo comes from. This article also covers the rectum and cecum as both have a similar mucosa.

It commonly comes to pathologists because there is a suspicion of colorectal cancer or a known history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

An introduction to gastrointestinal pathology is found in the gastrointestinal pathology article. The anus and ileocecal valve are dealt with in separate articles.

Technically, the rectum and cecum are not part of the colon. Thus, inflammation of the rectum should be proctitis and inflammation of the cecum should be cecitis.

Common clinical problems

Obstruction

Top three (in adults):[1]

- Neoplasia.

- Volvulus (cecal, sigmoid).

- Diverticular disease + stricture formation.

Bleeding

Mnemonic CHAND:[2]

- Colitis (radiation, infectious, ischemic, IBD (UC >CD), iatrogenic (anticoagulants)).

- Hemorrhoids.

- Angiodysplasia.

- Neoplastic.

- Diverticular disease.

Infectious colitis with bleeding - causes:

- Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) -- commonly 0157:H7.

- Campylobacter jejuni.

- Clostridium difficile.

- Shigella.

Infectious colitis in the immunosuppressed:

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV).[3]

Images:

Grossing

Types of specimens

Introduction to colorectal surgery:

- Colonic resection - remove a piece of large bowel.

- Total colectomy - leaves rectum and anus.[5]

- Subtotal colectomy - part of colon removed --or-- some of the rectum remains.

- Right hemicolectomy - right colon + distal ileum.

- Lower anterior resection (LAR) - proximal rectum +/- sigmoid (for proximal rectal malignancies).

- Specimens have should have intact mesorectum - total mesorectal excision (TME) - reduces local recurrence.[6]

- Abdominoperineal resection (APR) - anus + rectum - results in a permanent stoma (for distal rectal malignancies).

- Stoma - these are often done emergently and then get cut-out after the patient's condition has settled.

Images

Identifying the specimen

- Transverse colon - has omentum.

- Ascending colon - usu. comes with ileocecal valve and a bit of ileum.

- Descending colon - has a bare area.

- Rectum - has adventitia.

Images

Lymph nodes

- One should get at least 12 lymph nodes if it is cancer.[9]

Quirke method

Standard method

- Bowel is prep'ed by opening it along the antimesenteric side.

- Dimensions - length, circumference at both margins.

- Radial margin/circumferential margin - should be painted.

- Rectum starts/sigmoid ends @ place where serosa ends on the posterior aspect of the bowel.

- The proximal, anterior aspect of the rectum has serosa, i.e. it is not painted.

- Rectum starts/sigmoid ends @ place where serosa ends on the posterior aspect of the bowel.

Common non-neoplastic disease

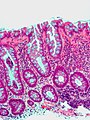

Colorectal polyps

Polyps are the bread & butter of GI pathology. They are very common.

Main types:

- Hyperplastic - most common, benign.

- Adenomatous - quite common, pre-malignant.

- Hamartomatous - rare, weird & wonderful.

- Inflammatory, AKA inflammatory pseudopolyps - associated with IBD.

Most common (images):

Ischemic colitis

Diverticular disease

Pseudomembranous colitis

Volvulus

General

- Uncommonly comes to pathology.

- It is essentially a radiologic diagnosis.

- In the context of autopsy, it is a gross diagnosis.

Gross

- Intestine folded over itself - typically leads to ischemia.

Images:

Microscopic

Features:

- +/-Ischemic changes and/or necrosis.

DDx - essentially anything that causes ischemia:

- Embolus.

- Thrombosis.

- Vasculitis.

Sign out

RECTOSIGMOID, RESECTION: - MURAL ISCHEMIA WITH PERFORATION, SEROSITIS, MICROABSCESS FORMATION AND POORLY FORMED PSEUDOMEMBRANES. - SUBMUCOSAL FIBROSIS. - NEGATIVE FOR MALIGNANCY. COMMENT: The findings are consistent with volvulus and the submucosal fibrosis suggests this may have been recurrent.

Inflammatory diseases

Inflammatory bowel disease

The bread 'n butter of gastroenterology. A detailed discussion of IBD is in the inflammatory bowel disease article. It comes in two main flavours (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis).

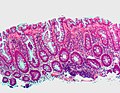

Microscopic

Features helpful for the diagnosis of IBD - as based on a study:[13]

- Basal, i.e. crypt base, plasmacytosis with severe chronic inflammation,

- Crypt architectural abnormalities, and

- Distal Paneth cell metaplasia.

Microscopic colitis

- Microscopic colitis may refer to a microscopic manifestation of an unspecified disease process that can be apparent macroscopically. This section links to a pair of diseases (lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis) that are considered to only have microscopic manifestations and characteristic clinical presentation.

Diversion colitis

Eosinophilic colitis

- Abbreviated EC.

Infectious

Infectious colitis

- This section covers non-specific colitides that appear to have an infective etiology.

General

- Common.

- Diarrhea - typical symptom.

Gross

- +/-Erythema on endoscopy.

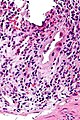

Microscopic

Features:

- Neutrophils predominant - key feature.[16]

- The neutrophils are often superficial - they go to were the bad guys are.

- No architectural distortion - if acute.

DDx:

- Inflammatory bowel disease - lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate predominant,[16] usually has chronic changes.

- Ischemic colitis.

- Medications - focal neutrophils.

- Lymphocytic colitis - lymphocytes with a squiggly nucleus, may be confused with neutrophils.

- Specific causes of infective colitis - with a distinctive morphology.

- CMV colitis - esp. in the immunodeficient.

- Pseudomembranous colitis - usu. due to C. difficle, has characteristic gross & microscopic appearance.

- Intestinal spirochetes.

- Amebiasis.

- Strongyloidiasis.

- Cryptosporidiosis.

IHC

Done if the patient is immunosuppressed, or there is clinical or morphological suspicion:

Sign out

ASCENDING COLON, BIOPSY: - MILD ACTIVE COLITIS, SEE COMMENT. COMMENT: There is are no granulomas. The crypt architecture is normal. A benign lymphoid nodule is present. The differential diagnosis includes infective etiologies, early inflammatory bowel disease and ischemia. The histomorphology is more in keeping with an infective etiology as neutrophils are a predominant feature; however, clinical correlation is required.

Cytomegalovirus colitis

- Abbreviated CMV colitis.

General

- Uncommon.

- Immunosuppressed population at risk, e.g. transplant recipients, individuals with HIV.

Microscopic

Features:

- Enlarged nucleus - classically in endothelial cells.

DDx:

- Infectious colitis without a distinctive morphology.

- CMV colitis superimposed on inflammatory bowel disease.

Images

www:

IHC

- CMV +ve.

Others:

- HSV-1.

- HSV-2.

- VZV.

- EBV.

Intestinal spirochetosis

- AKA intestinal spirochetes; more specifically colonic spirochetes, colonic spirochetosis.

Amebiasis

- May also be spelled amoebiasis.

Cryptosporidiosis

General

- Usually in immune incompetent individuals, e.g. HIV/AIDS.

Microscopic

Features:

- Uniform spherical nodules 2-4 micrometres in diameter, typical location - GI tract brush border.

- Bluish staining of brush border key feature - low power.

Rectal pathology

Solitary rectal ulcer

- AKA solitary ulcer syndrome of the rectum, abbreviated SUS.

- AKA solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

- Mucosal prolapse syndrome may be used as a synonym; however, it encompasses other entities.[18]

General

- Clinically may be suspected to a malignancy - biopsied routinely.

- Mucosal ulceration.

- "Three-lies disease":[19]

- May not be solitary.

- May not be rectal -- can be in left colon.

- May not be ulcerating -- non-ulcerated lesions: polypoid and/or erythematous.

Note: Each of the words in solitary rectal ulcer is a lie.

Epidemiology

- Typically younger patients - average age of presentation ~30 years in one study.[20]

- Rare.

Clinical presentation

- Usually presents as BRBPR ~ 85% of cases.[20]

- Abdominal pain present in approx. 1/3.[20]

- May be very painful.

Treatment:

- Usually conservative, i.e. non-surgical.

- Resection - may be done for fear of malignancy.

Gross

- Classically, anterior or anterolateral wall of the rectum.[19]

Microscopic

- Fibrosis of the lamina propria.

- Thickened muscularis mucosa with abnormal extension to the lumen.

- +/-Mucosa ulceration.

- +/-Submucosal fibrosis.

DDx:

- Inflammatory pseudopolyp (inflammatory polyp).

- Associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

- Rectal prolapse.

- Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.

IHC

- p53 -ve.

- May be used to help exclude adenocarcinoma.

Rectal prolapse

Neoplastic disease

Colorectal Tumours

These are very common. The are covered in a separate article entitled colorectal tumours.

Neuroendocrine tumour

- AKA carcinoid.

Goblet cell carcinoid

- Described in detail in the appendix article.

- AKA crypt cell carcinoma.

- Biphasic tumour; features of carcinoid tumour and adenocarcinoma.

Other

Colonic pseudo-obstruction

Pseudomelanosis coli

- AKA melanosis coli.

Angiodysplasia

General

- Causes (lower) GI haemorrhage.

- Generally, not a problem pathologists see.

- May be associated with aortic stenosis; known as Heyde syndrome.[22]

Epidemiology:

- Older people.

Etiology:

- Thought to be caused by the higher wall tension of cecum (due to larger diameter) and result from (intermittent) venous occlusion/focal dilation of vessels.[23]

Gross

- Cecum - classic location.

Note:

- Crohn's disease - may mimic angiodysplasia radiographically.[24]

Microscopic

Features:[24]

- Dilated vessels in mucosa and submucosa.

Drugs

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate

- AKA Kayexalate.

General

- Used to treat hyperkalemia - as may be seen in renal failure.

Microscopic

Features:[25]

- Purple blobs on H&E stain - look somewhat like calcium phosphate.

- Can cause focal necrosis.

Image

Graft-versus host disease

- Abbreviated as GVHD.

- Seen in the context of bone marrow transplants.

Bowel transplant

The histology of bowel transplant rejection is identical to GVHD - see GVHD.

Chronic constipation

- This section deals with chronic constipation that has no apparent cause.

General

General differential diagnosis for constipation:

- Tumour.

- Adhesions - due to previous surgery.

- Neuropathy.[26]

- Congenital defect (Hirschsprung's disease).

- Myopathy.[26]

- Medications/substance use.

- Idiopathic.

Gross

- No changes.

Microscopic

Features:

- Colon within normal limits.

- Look for the Ganglion cells (submucosal plexus, myenteric plexus).

- Look for interstitial cells of Cajal (with CD117) - typically most common around the myenteric plexus.[27]

Negatives:

- No significant vascular disease.

- No fibrosis.

- No loss of muscle.

Stains & IHC

Work-up if no tumour is identified:[28][29]

- Routine H&E.

- Smooth muscle actin - confirm myocyte loss.

- Gomori trichrome - examine connective tissue.

- CD117 - to look for the interstitial cells of Cajal.

- <50% the expected = abnormal.[29]

- Normal numbers not defined.

- <50% the expected = abnormal.[29]

- HU - neuronal marker.[30]

Sign out

- A long list of things to report is contained the recommendation of a working group.[29]

- Most pathology practises do not report much.

TERMINAL ILEUM, CECUM, COLON (ASCENDING, TRANSVERSE AND SIGMOID), COLECTOMY: - SMALL BOWEL, CECUM, AND COLON WITHIN NORMAL LIMITS. - FOUR LYMPH NODES NEGATIVE FOR MALIGNANCY ( 0 POSITIVE / 4 ). - NEGATIVE FOR DYSPLASIA AND NEGATIVE FOR MALIGNANCY. COMMENT: Several stains were done: CD117: interstitial cells of Cajal present, no apparent decrease. SMA: no significant myocyte loss. Gomori trichrome: no abnormal fibrosis apparent. Tau: no abnormalities apparent.

See also

References

- ↑ URL: http://www.emedicine.com/EMERG/topic65.htm. Accessed on: 28 June 2011.

- ↑ TN 2007 G29.

- ↑ Golden MP, Hammer SM, Wanke CA, Albrecht MA (September 1994). "Cytomegalovirus vasculitis. Case reports and review of the literature". Medicine (Baltimore) 73 (5): 246–55. PMID 7934809.

- ↑ Kandiel A, Lashner B (December 2006). "Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101 (12): 2857–65. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00869.x. PMID 17026558.

- ↑ http://www.allaboutbowelsurgery.com/shared/stoma_care/stoma_surgery/procedures/surgery_colon/subtotal.htm

- ↑ Arbman, G.; Nilsson, E.; Hallböök, O.; Sjödahl, R. (Mar 1996). "Local recurrence following total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer.". Br J Surg 83 (3): 375-9. PMID 8665198.

- ↑ Lester, Susan Carole (2010). Manual of Surgical Pathology (3rd ed.). Saunders. pp. 339. ISBN 978-0-323-06516-0.

- ↑ URL: http://www.bartleby.com/107/249.html. Accessed on: 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Stewart AK, et al. (September 2008). "Lymph node evaluation as a colon cancer quality measure: a national hospital report card". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100 (18): 1310–7. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn293. PMID 18780863. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/581463.

- ↑ West NP, Morris EJ, Rotimi O, Cairns A, Finan PJ, Quirke P (September 2008). "Pathology grading of colon cancer surgical resection and its association with survival: a retrospective observational study". Lancet Oncol. 9 (9): 857–65. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70181-5. PMID 18667357.

- ↑ West NP, Finan PJ, Anderin C, Lindholm J, Holm T, Quirke P (July 2008). "Evidence of the oncologic superiority of cylindrical abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer". J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (21): 3517–22. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5961. PMID 18541901.

- ↑ URL: http://pathsrvr.rockford.uic.edu/inet/GI/GI%20Station%201.htm. Accessed on: 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Tanaka M, Riddell RH, Saito H, Soma Y, Hidaka H, Kudo H (January 1999). "Morphologic criteria applicable to biopsy specimens for effective distinction of inflammatory bowel disease from other forms of colitis and of Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 34 (1): 55–67. PMID 10048734.

- ↑ Tanaka M, Saito H, Kusumi T, et al (December 2001). "Spatial distribution and histogenesis of colorectal Paneth cell metaplasia in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease". J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (12): 1353–9. PMID 11851832. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0815-9319&date=2001&volume=16&issue=12&spage=1353.

- ↑ Rubio CA, Nesi G (2003). "A simple method to demonstrate normal and metaplastic Paneth cells in tissue sections". In Vivo 17 (1): 67–71. PMID 12655793.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Iacobuzio-Donahue, Christine A.; Montgomery, Elizabeth A. (2005). Gastrointestinal and Liver Pathology: A Volume in the Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology Series (1st ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 324. ISBN 978-0443066573.

- ↑ Karlitz, JJ.; Li, ST.; Holman, RP.; Rice, MC. (Jan 2011). "EBV-associated colitis mimicking IBD in an immunocompetent individual.". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8 (1): 50-4. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.192. PMID 21119609.

- ↑ Abid, S.; Khawaja, A.; Bhimani, SA.; Ahmad, Z.; Hamid, S.; Jafri, W. (2012). "The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases.". BMC Gastroenterol 12: 72. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-12-72. PMID 22697798.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Crespo Pérez L, Moreira Vicente V, Redondo Verge C, López San Román A, Milicua Salamero JM (November 2007). "["The three-lies disease": solitary rectal ulcer syndrome"] (in Spanish; Castilian). Rev Esp Enferm Dig 99 (11): 663–6. PMID 18271667. http://www.grupoaran.com/mrmUpdate/lecturaPDFfromXML.asp?IdArt=459864&TO=RVN&Eng=1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Chong VH, Jalihal A (December 2006). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: characteristics, outcomes and predictive profiles for persistent bleeding per rectum". Singapore Med J 47 (12): 1063–8. PMID 17139403. http://www.sma.org.sg/smj/4712/4712a7.pdf.

- ↑ Malik, AK.; Bhaskar, KV.; Kochhar, R.; Bhasin, DK.; Singh, K.; Mehta, SK.; Datta, BN. (Jul 1990). "Solitary ulcer syndrome of the rectum--a histopathologic characterisation of 33 biopsies.". Indian J Pathol Microbiol 33 (3): 216-20. PMID 2091997.

- ↑ Hui YT, Lam WM, Fong NM, Yuen PK, Lam JT (August 2009). "Heyde's syndrome: diagnosis and management by the novel single-balloon enteroscopy". Hong Kong Med J 15 (4): 301–3. PMID 19652242. http://www.hkmj.org/abstracts/v15n4/301.htm.

- ↑ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 854. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Hemingway, AP. (Apr 1988). "Angiodysplasia: current concepts.". Postgrad Med J 64 (750): 259-63. PMID 3054852.

- ↑ Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, Rashid A, Wu TT (May 2001). "Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings". Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 25 (5): 637-44. PMID 11342776. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0147-5185&volume=25&issue=5&spage=637.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Knowles, CH.; Farrugia, G. (Feb 2011). "Gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology in chronic constipation.". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 25 (1): 43-57. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.001. PMID 21382578.

- ↑ Streutker, CJ.; Huizinga, JD.; Driman, DK.; Riddell, RH. (Jan 2007). "Interstitial cells of Cajal in health and disease. Part I: normal ICC structure and function with associated motility disorders.". Histopathology 50 (2): 176-89. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02493.x. PMID 17222246. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02493.x/pdf.

- ↑ IAV. 15 December 2009.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Knowles, CH.; De Giorgio, R.; Kapur, RP.; Bruder, E.; Farrugia, G.; Geboes, K.; Gershon, MD.; Hutson, J. et al. (Aug 2009). "Gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology: guidelines for histological techniques and reporting on behalf of the Gastro 2009 International Working Group.". Acta Neuropathol 118 (2): 271-301. doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0527-y. PMID 19360428.

- ↑ Barami K, Iversen K, Furneaux H, Goldman SA (September 1995). "Hu protein as an early marker of neuronal phenotypic differentiation by subependymal zone cells of the adult songbird forebrain". J. Neurobiol. 28 (1): 82–101. doi:10.1002/neu.480280108. PMID 8586967.