Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

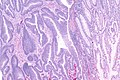

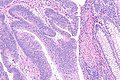

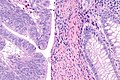

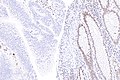

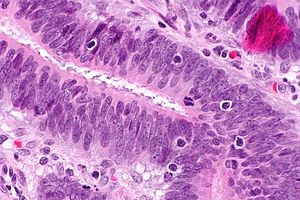

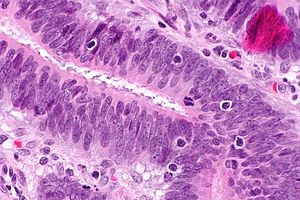

Intratumoural lymphocytic response in colorectal carcinoma, as may be seen in microsatellite instability. H&E stain. (WC)

Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer, often abbreviated MSI, is recognized as an important predictor of outcome in colorectal adenocarcinoma, and may be seen in the context of Lynch syndrome.

General

- Can be sporadic, i.e. non-syndromic.[1]

- Strong association with Lynch syndrome.[2][1]

Features:[3]

- Prognosis: slightly better than other CRC without MSI.

- Treatment implication: different response to chemotherapy.

MSI classification

MSI associated cancers can be classified into:[4][5]

- MSI-H >= 30% of loci have abnormality.

- MSI-L <30% of loci have abnormality.

Note:

- In the context of no chemotherapy, individuals with MSI-H tumours have a superior outcome to those with MSI-L tumours.[6]

- With chemotherapy the outcomes are similar.

Gross

Features:[3]

- Location: proximal colon, i.e. right-sided, predominance.

Microscopic

Features:[3]

- Lymphocytic infiltrate - see intratumoural lymphocytic response.

- Large peritumoural collections of lymphocytes - see peritumoural lymphocytic response.

- Pushing border.[7]

- Histomorphology:

- Poorly differentiated.

- Mucinous.

- Signet ring.

- Medullary.[8]

Molecular

Commonly associated abnormalities in the genes:

- MLH1.

- PMS2.

- MSH2.

- MSH6.

Less common abnormalities:

- PMS1.

- MLH3.

- MSH3.

Additional notes:

- Small subset of cases is caused by mutations in EPCAM, a gene adjacent to MSH2.

- EPCAM mutations lead to epigenetic silencing of MSH2.[9]

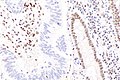

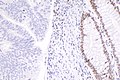

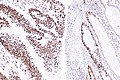

IHC

Immunostains are commonly done for:

- MLH1.

- PMS2.

- MSH2.

- MSH6.

Note:

- MSI testing (in the context of suspect Lynch syndrome) can be done on adenomatous polyps;[10] however, dysplasia should be present.[11]

- Sessile serrated adenomas without dysplasia should not be tested.

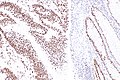

IHC interpretation

- Loss of nuclear staining in nuclei of the tumour implies a mutation.

- Nuclear staining = normal.

- Heterogenous MSH6 loss of staining is significant.[12]

MSI staining loss patterns:[13]

- MLH1 and PMS2 are often lost together, as MLH1 loss results in PMS2 loss.

- MSH2 and MSH6 are often lost together, as MSH2 loss results in MSH6 loss.

Implication of MSI staining loss patterns:

- PMS2 & MSH6 can be used as a screen.[13]

Etiology/significance loss of staining

- MSH2 loss (IHC stain -ve) - often associated with a germline mutation,[14] while mutations in MLH1 are usually sporatic.[15]

- PMS2 loss (IHC stain -ve) - often associated with a germline mutation,[16] may be due to MLH1 promoter hypermethylation.[17]

How to remember the more important MSI stuff:

- Groupings:

- The MSHs are paired together.

- PMS sucks... it's with the other one (MLH).

- The higher numbers in the pairings (PMS2, MSH6) are the screening tests (High Screen Pass).

- The 2s (MSH2, PMS2) are associated with germline mutations (Four legs good two legs bad!).

Images

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Heinimann, K. (2013). "Toward a Molecular Classification of Colorectal Cancer: The Role of Microsatellite Instability Status.". Front Oncol 3: 272. doi:10.3389/fonc.2013.00272. PMID 24199172.

- ↑ Mensenkamp, AR.; Vogelaar, IP.; van Zelst-Stams, WA.; Goossens, M.; Ouchene, H.; Hendriks-Cornelissen, SJ.; Kwint, MP.; Hoogerbrugge, N. et al. (Dec 2013). "Somatic mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 are a Frequent Cause of Mismatch-repair Deficiency in Lynch Syndrome-like Tumors.". Gastroenterology. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.002. PMID 24333619.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Boland CR, Goel A (June 2010). "Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer". Gastroenterology 138 (6): 2073–2087.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. PMID 20420947.

- ↑ Lawes DA, Pearson T, Sengupta S, Boulos PB (August 2005). "The role of MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in the development of multiple colorectal cancers". Br. J. Cancer 93 (4): 472–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602708. PMC 2361590. PMID 16106253. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2361590/.

- ↑ Guidoboni M, Gafà R, Viel A, et al. (July 2001). "Microsatellite instability and high content of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes identify colon cancer patients with a favorable prognosis". Am. J. Pathol. 159 (1): 297–304. PMC 1850401. PMID 11438476. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1850401/.

- ↑ Ribic, CM.; Sargent, DJ.; Moore, MJ.; Thibodeau, SN.; French, AJ.; Goldberg, RM.; Hamilton, SR.; Laurent-Puig, P. et al. (Jul 2003). "Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer.". N Engl J Med 349 (3): 247-57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022289. PMID 12867608.

- ↑ Pollet, A. 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Truta B, Chen YY, Blanco AM, et al. (2008). "Tumor histology helps to identify Lynch syndrome among colorectal cancer patients". Fam. Cancer 7 (3): 267–74. doi:10.1007/s10689-008-9186-8. PMID 18283560.

- ↑ Yamamoto, H.; Imai, K. (Jun 2015). "Microsatellite instability: an update.". Arch Toxicol 89 (6): 899-921. doi:10.1007/s00204-015-1474-0. PMID 25701956.

- ↑ Pino, MS.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Wildemore, BM.; Ganguly, A.; Batten, J.; Sperduti, I.; Iafrate, AJ.; Chung, DC. (May 2009). "Deficient DNA mismatch repair is common in Lynch syndrome-associated colorectal adenomas.". J Mol Diagn 11 (3): 238-47. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080142. PMID 19324997.

- ↑ Higuchi, T.; Jass, JR. (Jul 2004). "My approach to serrated polyps of the colorectum.". J Clin Pathol 57 (7): 682-6. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.015230. PMID 15220357.

- ↑ Graham, RP.; Kerr, SE.; Butz, ML.; Thibodeau, SN.; Halling, KC.; Smyrk, TC.; Dina, MA.; Waugh, VM. et al. (Oct 2015). "Heterogenous MSH6 loss is a result of microsatellite instability within MSH6 and occurs in sporadic and hereditary colorectal and endometrial carcinomas.". Am J Surg Pathol 39 (10): 1370-6. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000459. PMID 26099011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hall, G.; Clarkson, A.; Shi, A.; Langford, E.; Leung, H.; Eckstein, RP.; Gill, AJ. (2010). "Immunohistochemistry for PMS2 and MSH6 alone can replace a four antibody panel for mismatch repair deficiency screening in colorectal adenocarcinoma.". Pathology 42 (5): 409-13. doi:10.3109/00313025.2010.493871. PMID 20632815.

- ↑ Mangold E, Pagenstecher C, Friedl W, et al. (December 2005). "Tumours from MSH2 mutation carriers show loss of MSH2 expression but many tumours from MLH1 mutation carriers exhibit weak positive MLH1 staining". J. Pathol. 207 (4): 385–95. doi:10.1002/path.1858. PMID 16216036.

- ↑ A. Pollett. 2010.

- ↑ Vaughn CP, Robles J, Swensen JJ, et al. (May 2010). "Clinical analysis of PMS2: mutation detection and avoidance of pseudogenes". Hum. Mutat. 31 (5): 588–93. doi:10.1002/humu.21230. PMID 20205264.

- ↑ Kato, A.; Sato, N.; Sugawara, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kito, M.; Makino, K.; Sato, T.; Shimizu, D. et al. (Feb 2016). "Isolated Loss of PMS2 Immunohistochemical Expression is Frequently Caused by Heterogenous MLH1 Promoter Hypermethylation in Lynch Syndrome Screening for Endometrial Cancer Patients.". Am J Surg Pathol. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000606. PMID 26848797.