Medical liver disease

This article deals with medical liver disease. An introduction to the liver and approach is found in the liver article.

Every differential in liver pathology has "drugs"[1] -- if it isn't clearly malignancy.

Liver neoplasms are dealt with in the liver neoplasms article.

Medical liver biopsies are often non-specific, as the liver has the same appearance for many mechanisms of injury, especially when the injury is marked. The clinical history, serology and imaging are essential for proper interpretations in this domain of pathology.

Review of liver blood work

Inflammation activity

- ALT.

- AST.

Cholestatic markers

- ALP.

- GGT - used to assess whether the ALP is an "honest" value, elevated in cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis/decompensation

- PLT - low is suggestive of dysfunction.

- INR - high is bad, unless anticoagulated.

Other

- Bilirubin.

- Direct (AKA conjugated).

- Indirect (AKA unconjugated).

A short DDx of elevated:[2]

- Indirect:

- Gilbert syndrome.

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1.

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2.

- Direct:

- Rotor syndrome.

- Dubin-Johnson syndomre.

Viral hepatitis

- HBV DNA.

- HCV RNA.

- HBs Ag, HBs Ab, HBe Ag, HBe Ab.

- HCV Ab.

Others:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) - especially in the immune incompetent.

Hepatitis B

Meaning & utility of the various Hepatitis B tests:[3][4]

| Test name | Location | Positive test | Negative test | Usual question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBs Ag | Surface | Virus active | No active infection | Active infection? |

| HBs Ab | Surface | Exposed OR vaccinated | No exposure OR no vaccine OR loss of Ab | Immunization status? |

| HBe Ag | Virus core | Infect. w/ viral replication | No active infection | Active infect. w/ viral replication? |

| HBe Ab | Virus core | Exposed to virus | Infect. w/o antibody response OR not exposed | Immune response to infection? |

| HBV DNA | - | Active | Not active/no exposure | Viral load/how active? |

| HBc Ab | Virus core | Virus active/previous exposure | No exposure | Early active infection? |

Notes:

- HBc Ab may test for acute (IgM) or chronic infection - dependent on specific antibody test; it is often used to look for early infection.[4]

- Carriers of hepatitis B: HBs Ag +ve, HBs Ab -ve, HBc Ag -ve, HBc Ab +ve, HBe Ag -ve, HBe Ab +ve.[5]

Markers for rare liver diseases

- Ceruloplasm - low think Wilson's disease; typical value for Wilson's ~ 0.12 g/L.

- <0.20 g/L is a criteria for Wilson's disease.[6]

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin - if low think deficiency.

Hemosiderosis

- Ferritin - high.

- Iron saturation - high.

Causes:

- Hemochromatosis.

- Hemolysis, chronic.

- Cirrhosis.

Medical imaging

Blood flow:[7]

- Hepatopedal flow = normal portal vein flow.

- Hepatofugal flow = reversed portal vein flow.

Interventional measurements

Wedged to free hepatic venous pressure:[8]

- Normal = 1-4 mmHg.

- Elevated in portal hypertension.

Liver biopsy

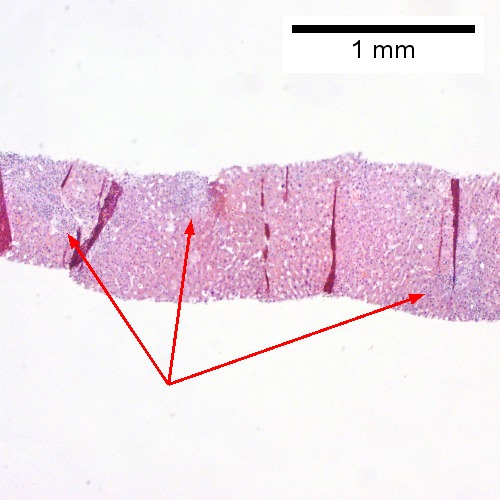

Medical liver biopsy adequacy

Liver biopsy specimens should be:[9]

- 2.0 cm in length and contain 11-15 portal tracts,

- The core should be deeper than 1.0 cm from the liver capsule; specimens close to the capsule may lead to over grading of fibrosis.

Reporting

Specimen, procedure: - Diagnosis.

The diagnosis usually contains grading and staging information, e.g. activity 2 /4, Laennec fibrosis stage 1 /4.

In the context of medical liver disease:

- Grade = inflammation/activity.

- Stage = severity of fibrosis/architectural changes.

Notes:

- The term "acute" is infrequently used in liver pathology.

- In the liver: neutrophils is not acute -- unlike most elsewhere in the body.[10]

A microscopic checklist

Size of biopsy: Adequate Fragmentation: Absent Fibrosis: Stage 2-3/4, mostly stage 2 Fibrous septa: Present Septa with curved contours: Present – focally only Large droplet steatosis (% of hepatocytes): Present, moderate 60% Ballooning of hepatocytes: Present, rare Mallory-Denk bodies: Present, rare Portal inflammation: Present Interface activity: Minimal (0-1/4) Lobular necroinflammation: Minimal Ducts: Present in normal numbers Duct injury: Absent Ductular reaction: Absent Cholestasis: Absent Terminal hepatic venules: Present Iron stain: Absent Ground glass cells with routine stains: Absent PASD for alpha-1 antitrypsin droplets: Negative

Viral hepatitis

These are common. The diagnoses are based on serology. The serology is covered in the viral hepatitis section in the liver pathology article.

Typically classified as:[11][12]

- Acute < 6 months duration.

- Chronic > 6 months duration.

Hepatitis A

- Infection is self-limited, i.e. not persistent.

- May present as fulminant hepatic necrosis.

- Usually asymptomatic in children.[13]

- Serology is diagnostic.

Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis B virus, abbreviated HBV, redirects here.

Hepatitis C

Other infections

- Hydatid disease (Hydatid cyst).

- Ascaris.

- Fasciola

Hydatid disease

- AKA hydatid cyst.

General

- Etiology: Echinococcus.

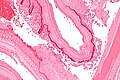

Microscopic

Features:

- Laminated wall +/- calcification.[14]

- Organisms -- see Echinococcus.

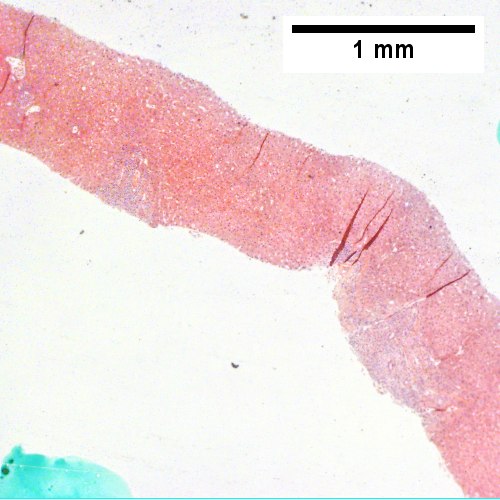

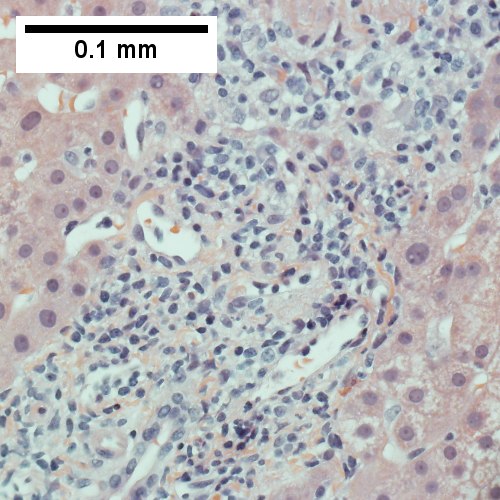

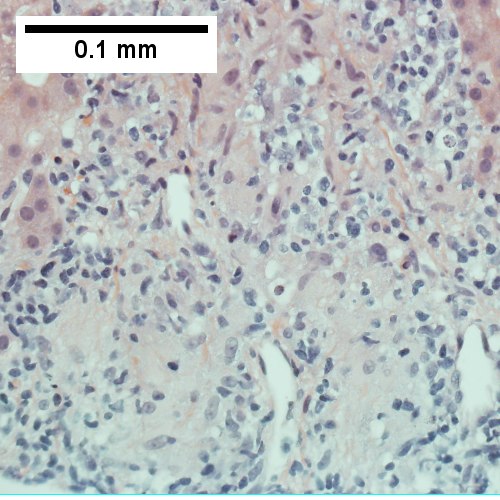

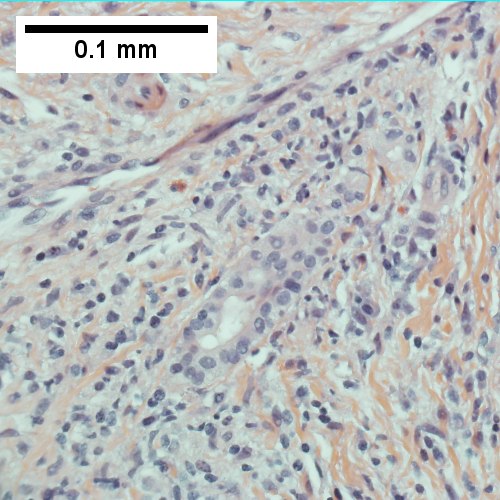

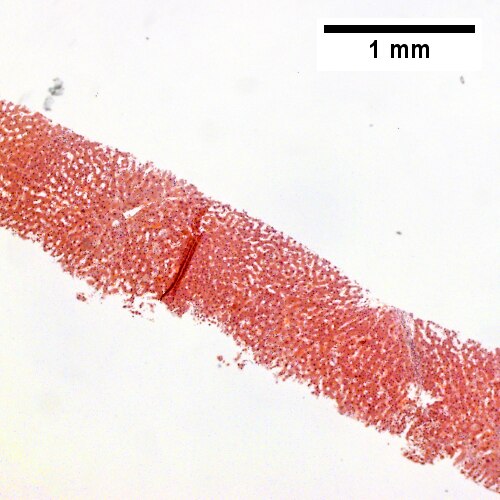

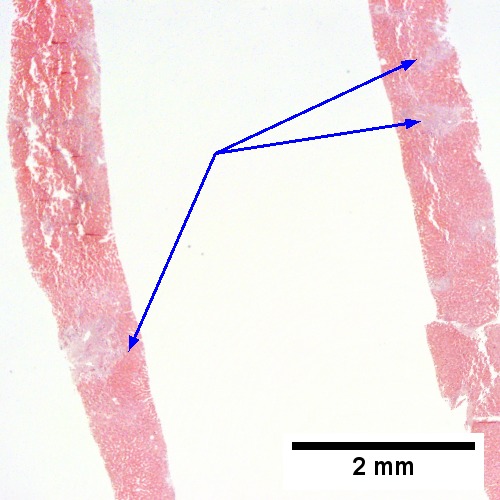

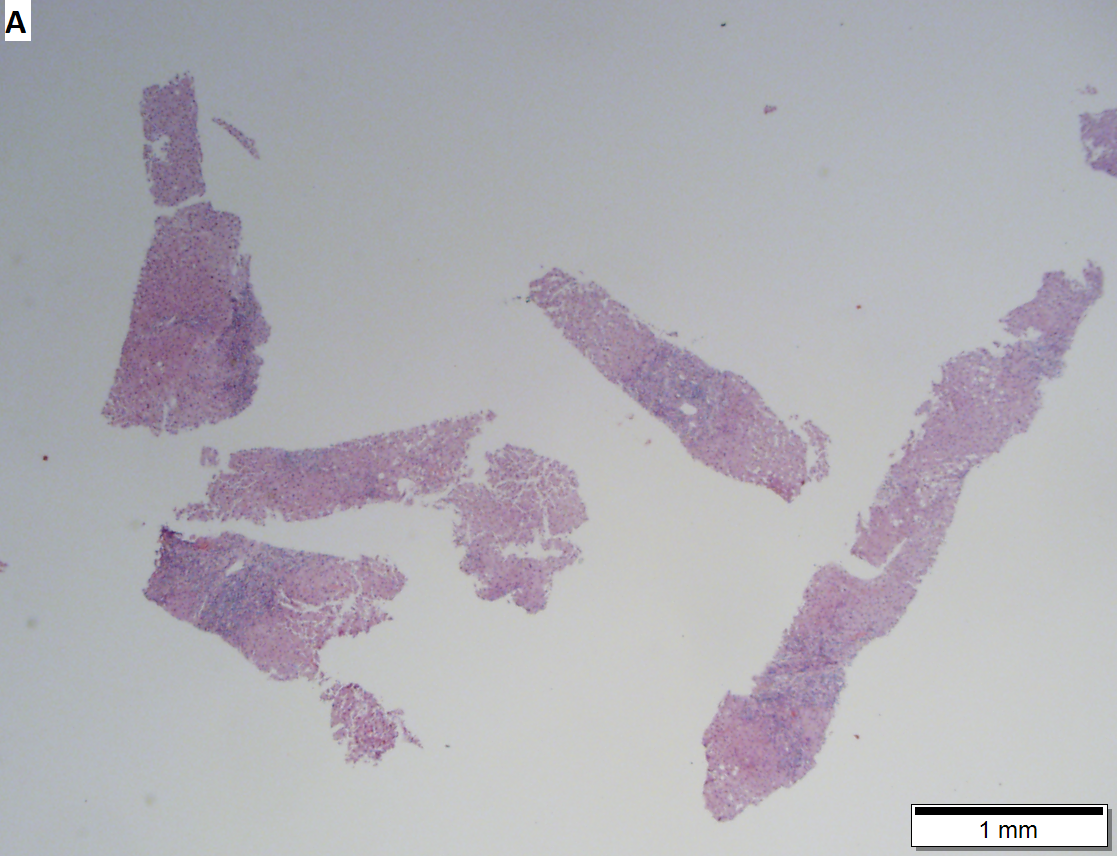

Images

www:

Abscess

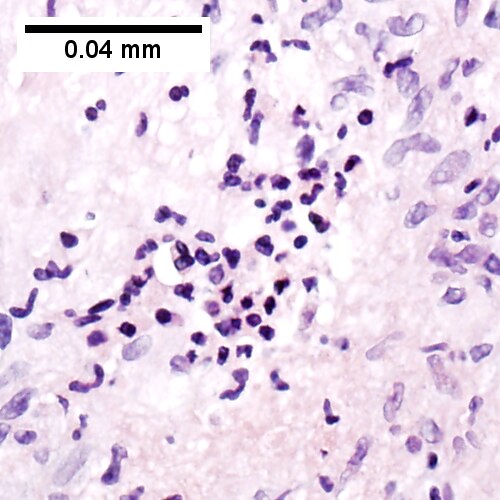

A.

B.

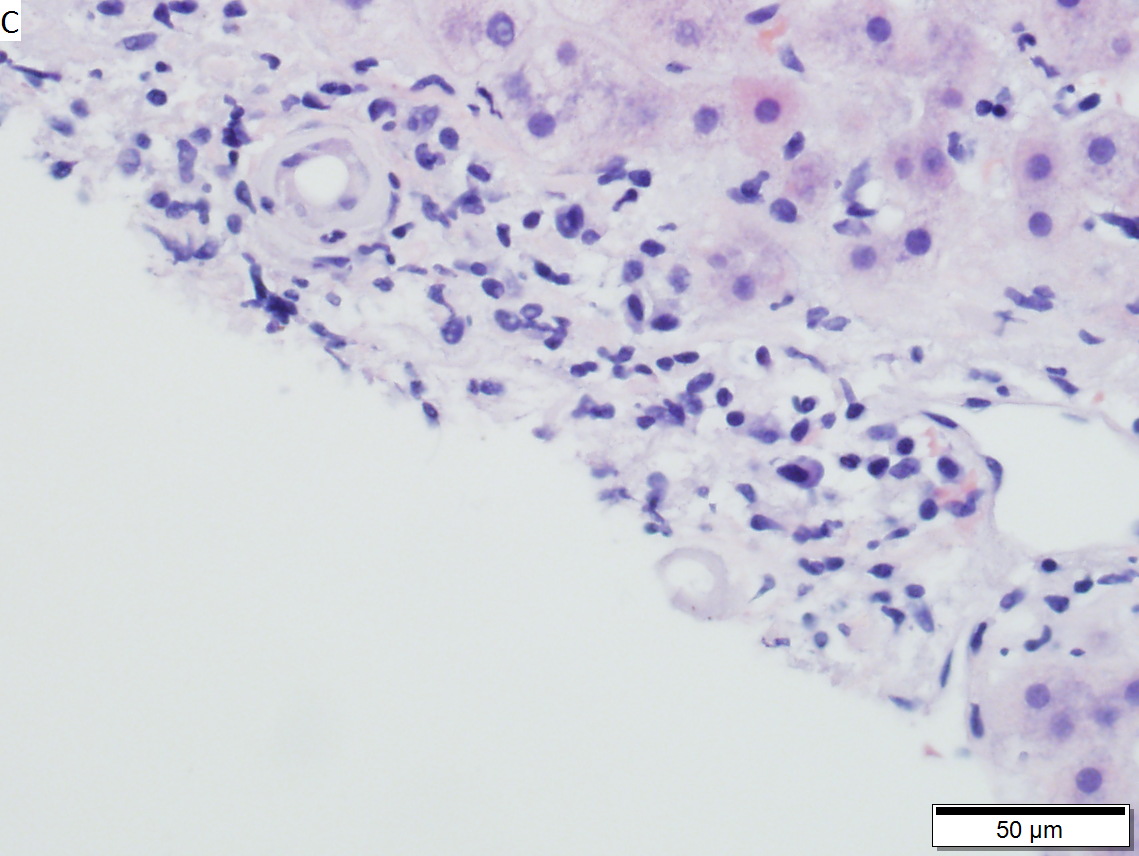

C.

D.

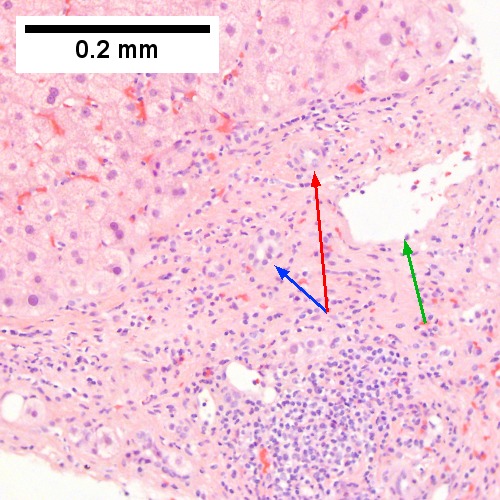

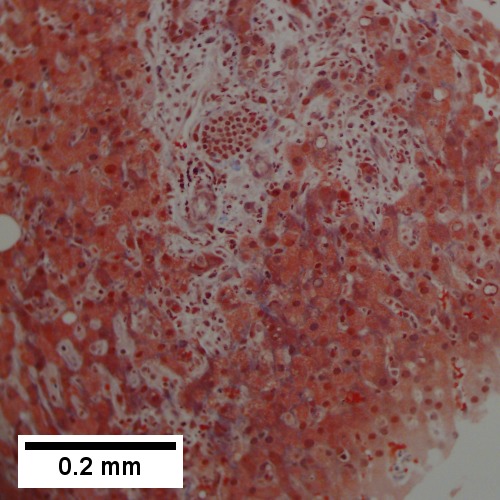

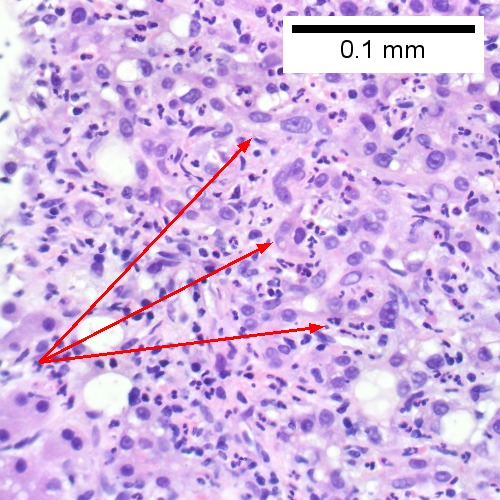

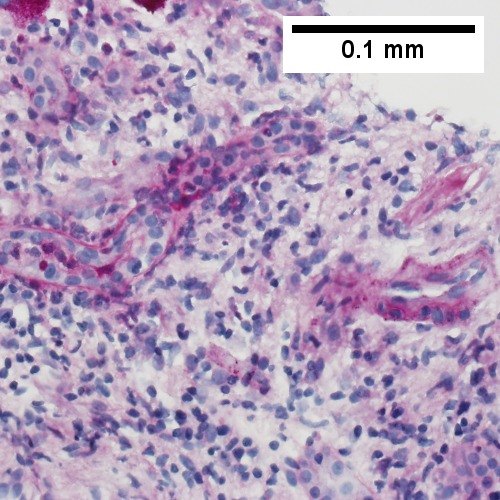

Abscess. A. A process replaces most of the liver parenchyma. B. Fibrinopurulent exudate apposes granulation tissue. C. Neutrophils lie in widened sinusoids. D. Trichrome shows collagenization of spaces of Disse. Scarring about an abscess or other mass lesion should not be interpreted as reflective of the liver in general (LR 200X).

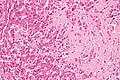

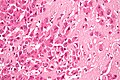

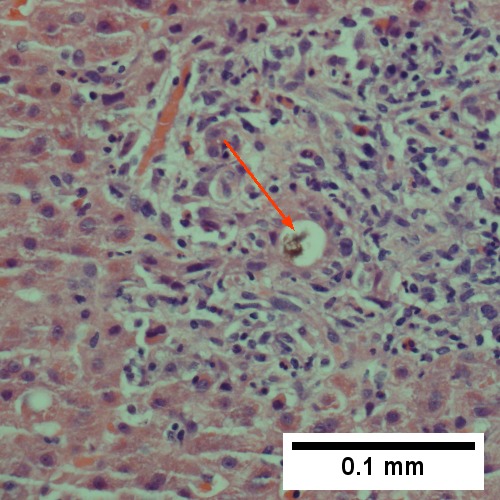

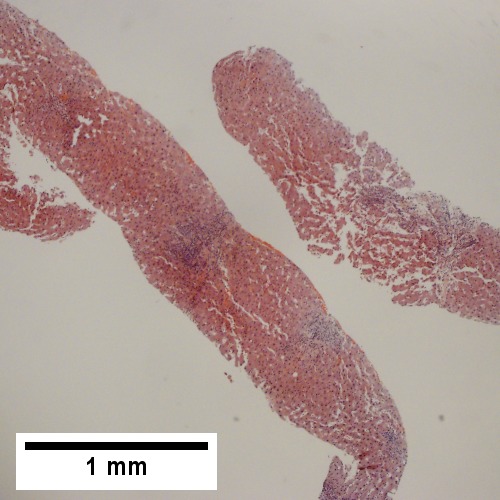

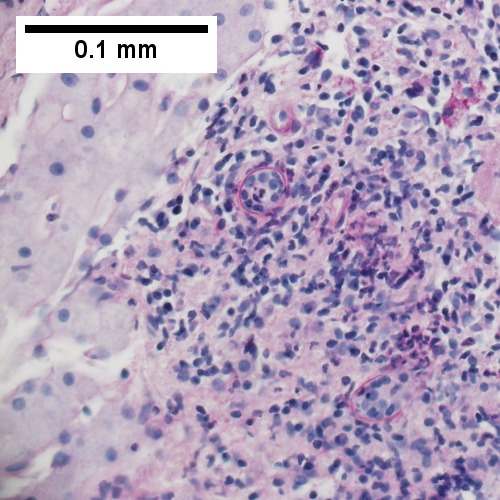

Coccidiomycosis

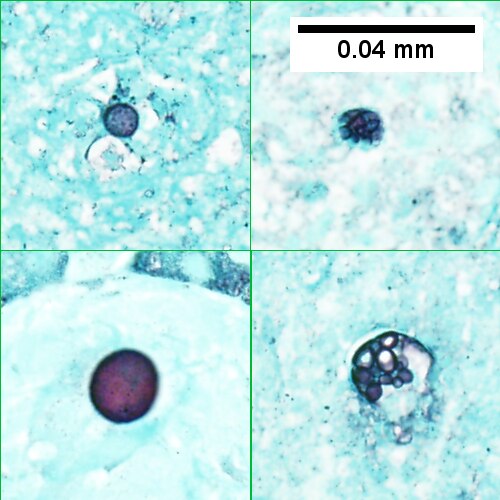

A.

B.

C.

D.

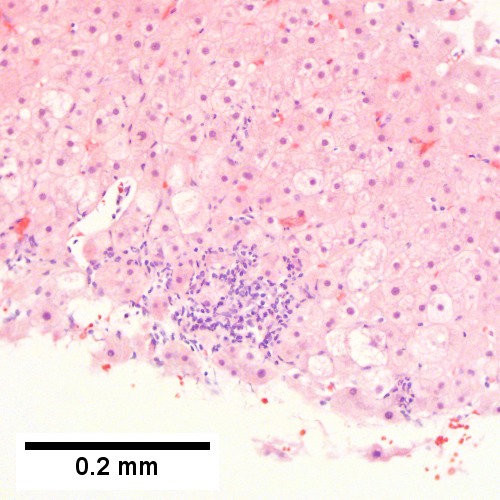

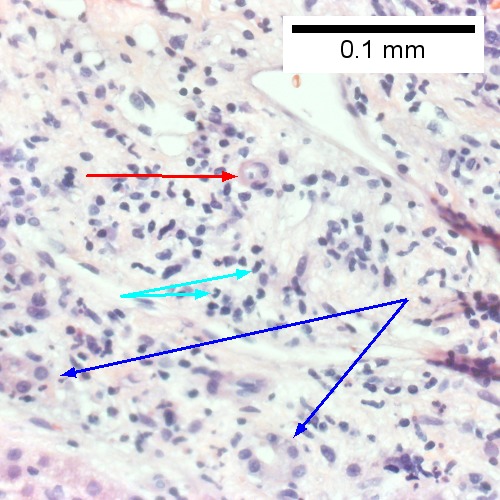

Coccidiomycosis. A. Note the granulomas in otherwise undisturbed liver (UL). B. Granuloma with centrally crowded cells & lady slipper macrophage nuclei. C. Center of granuloma with pyknotic macrophage nuclei, "necrotizing". D. Organisms on GMS stain.

Metabolic and toxic

Alcoholic liver disease

General

- Acute and/or chronic liver changes due to excessive alcohol use - includes:

Classic lab findings in EtOH abusers

- AST & ALT elevated with AST:ALT=2:1.

- GGT elevated.

- MCV increased.

Gross pathology/radiologic findings

- Classically micronodular pattern.

- May be macronodular.

Microscopic

See:

- Steatohepatitis section and ballooning degeneration section.

Features:

- Often zone III damage.

- Cholestatsis common, i.e. yellow staining.

- NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) usu. does not have cholestasis.[17]

- Fibrosis starts at central veins.

- Neutrophils (often helpful) -- few other things have PMNs. (???)

- Neutrophils cluster around cells with Mallory hyaline.

Images

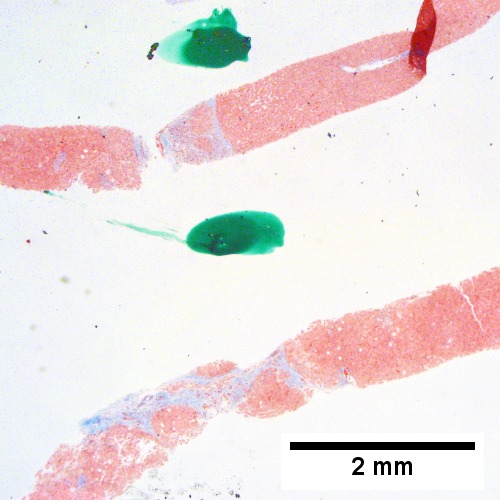

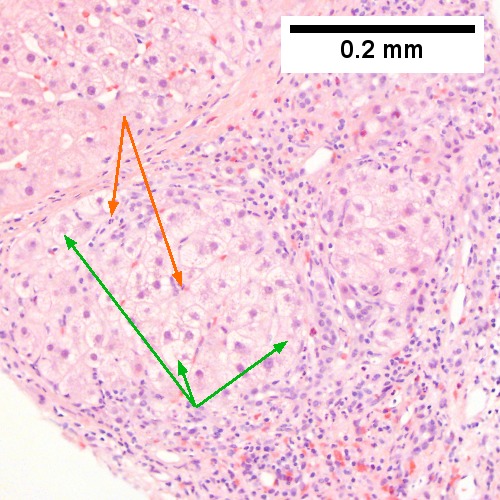

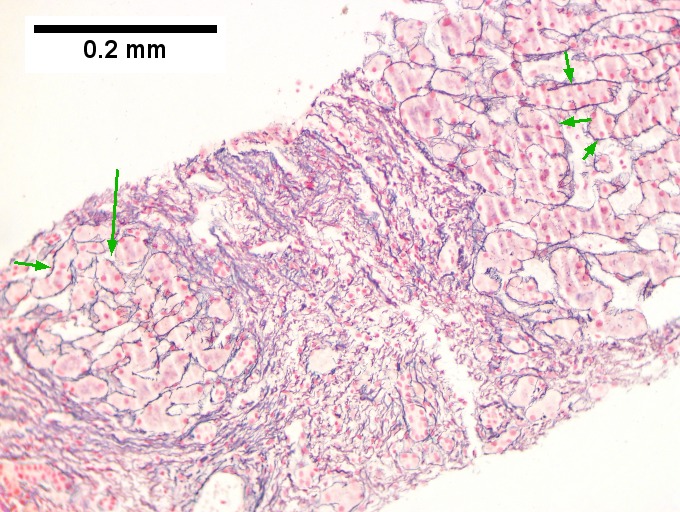

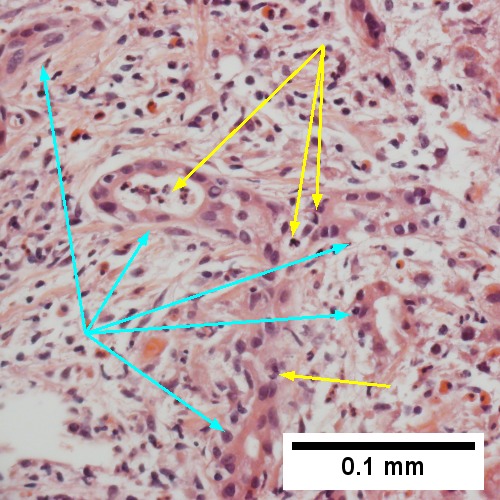

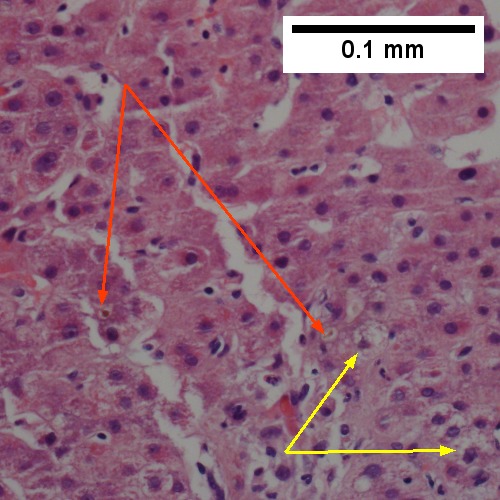

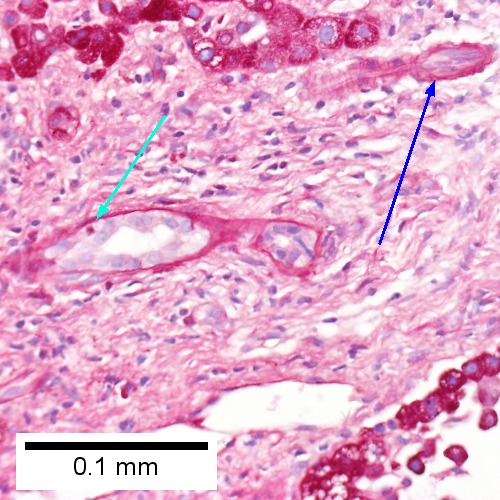

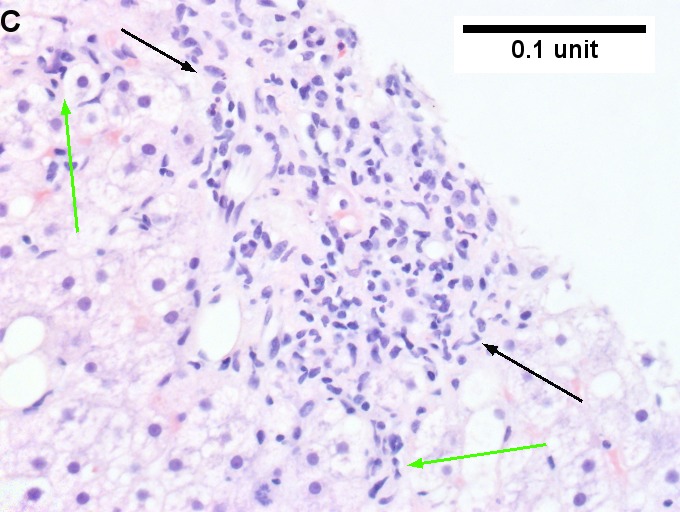

Alcoholic hepatitis with Metavir stage IV fibrosis (advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis).

A. Trichrome shows relatively non-inflamed fibrous bands, as well as [between green dots] nodules. The lack of regeneration throughout might have precluded a diagnosis of cirrhosis, but stage IV fibrosis under the Metavir system is justified. B. Reticulin shows regenerative nodules [left] with mostly two or more nuclei between black lines juxtaposed to non-regenerative hepatocytes on the right, without piecemeal necrosis. C. Regenerative nodules show occasional neutrophils [red arrow] and cytoplasmic tufts of ballooned cells, sometimes possibly Mallory hyalin [green arrows]. D. Triads (note vein [green arrow], artery [yellow arrow], and interlobular bile duct [blue arrow]) generally showed little or no interface hepatitis, even when expanded by fibrosis and inflamed. E. Occasional foci of spotty necrosis were seen. F. This edge of an inflamed triads shows neutrophils about proliferated bile ducts [red arrows], as well as Mallory-Denk bodies [blue arrows].

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

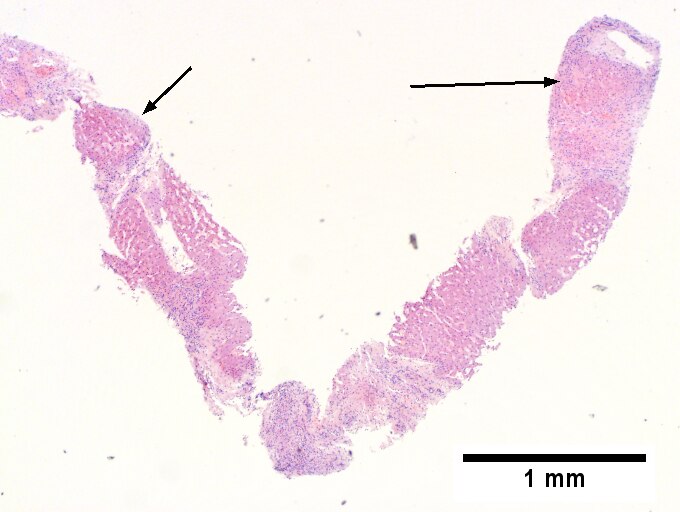

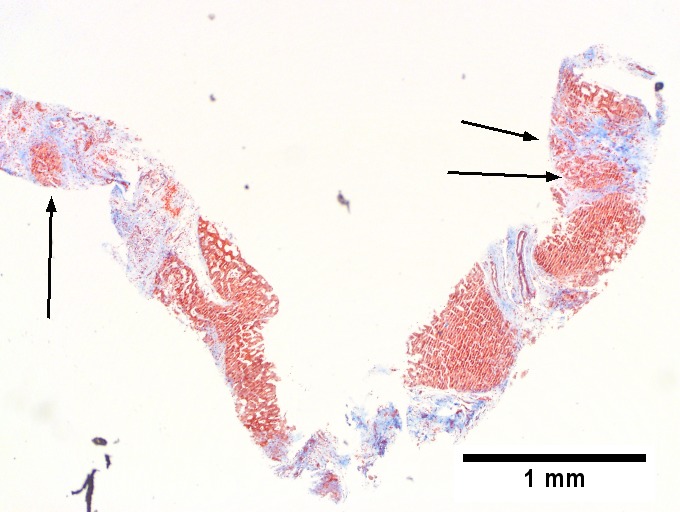

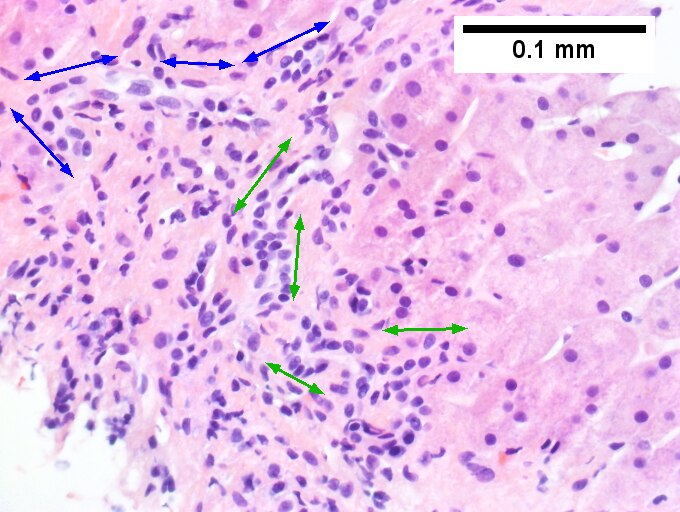

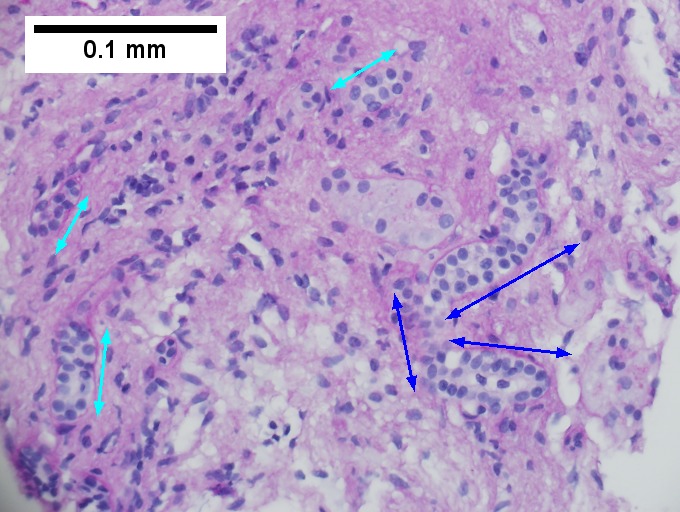

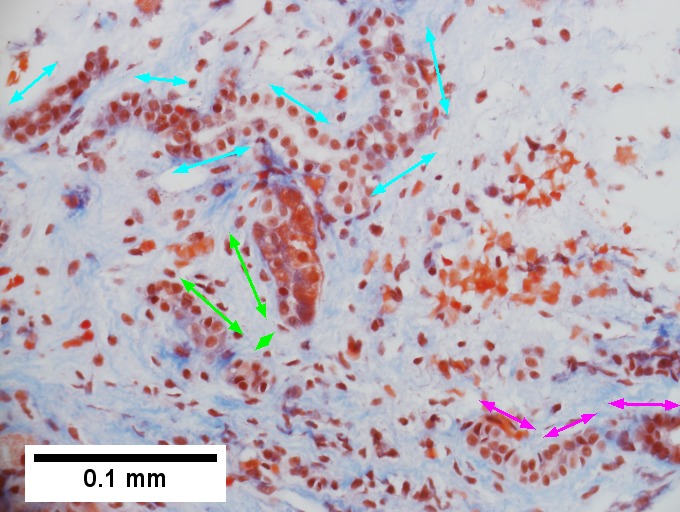

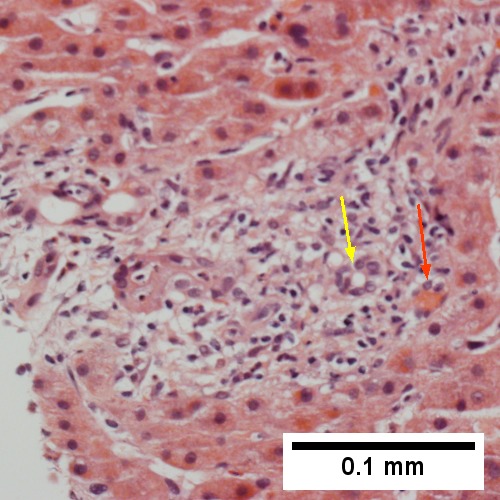

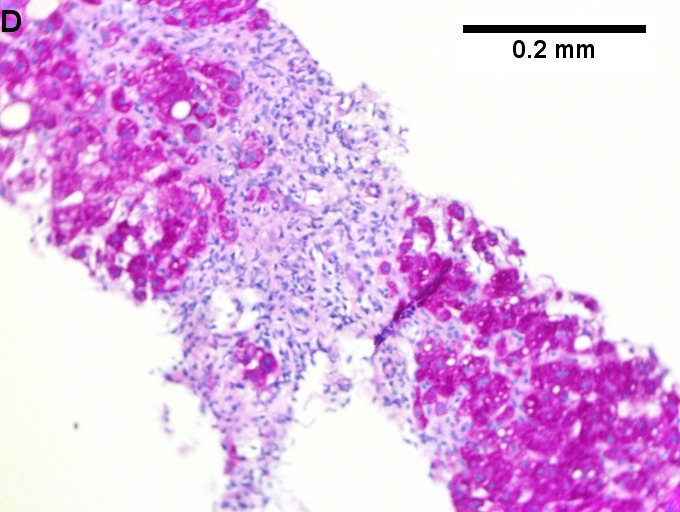

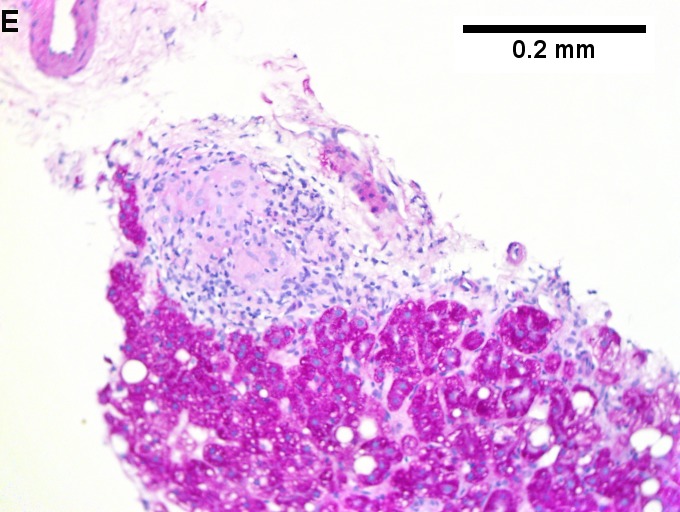

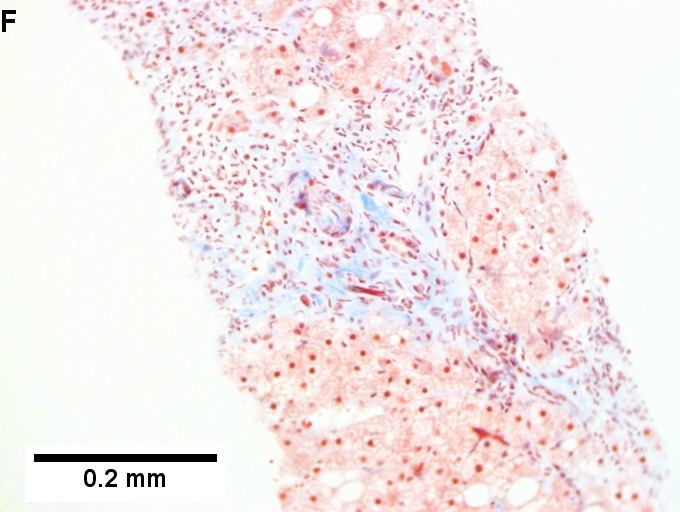

Definite cirrhosis in an alcoholic. A. Hepatocyte free bands parse tissue, with occasional definite islands [arrows]. B. Trichrome establishes blue fibrosis about isles [arrows]. C. Reticulin stain shows nodules with regeneration, wherein a large proportion of them are at least two nuclei thick [arrows]. D. Bile duct proliferation can be difficult, sometimes mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Follow the double headed arrows to see how the ductules can be seen to proliferate from a single sources, with all ducts being complete, without necrotic epithelial cells. E. PAS with distase can help, as cholangiocarcinoma generally lacks the red rim of proliferating bile ductules [arrows]; again note the connections that can be made between the ductule openings by the blue double headed arrows. The cyan double headed arrows show general parallelism, consistent with uniform directionality induced by extrinsic force, not a neoplastic spread. F. Trichrome shows the most difficult focus. Double headed arrows display the connectivity seen before of the proliferated bile ductules. Note that numerous pairs of adjacent perpendicular glands without a head to foot appearance are not seen that would indicate the disorderly spread of cholangiocarcinoma.

A.

B. ![Trichrome stain shows periportal fibrosis [red arrowheads] (200X).](/w/images/thumb/c/cd/2_ALC_2_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-2_ALC_2_680x512px.tif.jpg)

C. ![PAS with diastase stain shows proliferated bile ductules [blue arrowheads] in stroma with mixed inflammatory infiltrate (400X)](/w/images/thumb/5/5b/3_ALC_2_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-3_ALC_2_680x512px.tif.jpg)

D. ![Neutrophils about ballooned hepatocyte (satellitosis) [yellow arrowheads]. Councilman bodies [green arrowheads] (400X).](/w/images/thumb/7/75/4_ALC_2_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-4_ALC_2_680x512px.tif.jpg)

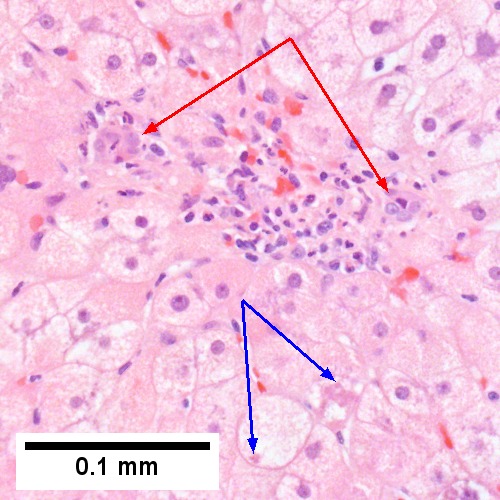

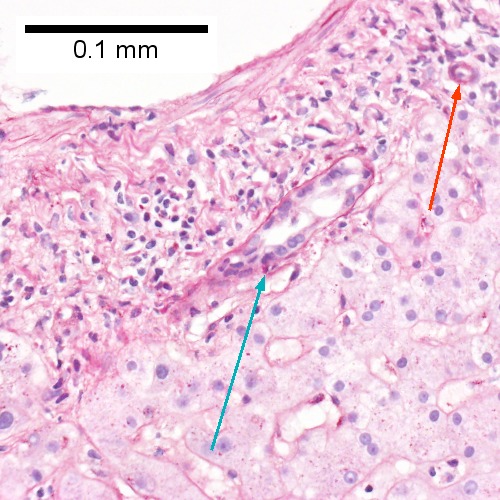

Alcoholic hepatitis without cirrhosis. No history of viral disease. AMA negative. A. Expanded, inflamed triads with increased bile duct/vascular openings. Mild steatosis. B. Trichrome stain shows periportal fibrosis [red arrowheads]. C. PAS with diastase stain shows proliferated bile ductules [blue arrowheads] in stroma with mixed inflammatory infiltrate. D. Neutrophils about ballooned hepatocyte (satellitosis) [yellow arrowheads]. Councilman bodies [green arrowheads].

Notes:

- If portal inflammatory infiltrates more than mild, r/o other causes i.e. viral hepatitis.

- Mallory bodies once thought to be characteristic; now considered non-specific and generally poorly understood.[18]

- Some consider alcoholic liver disease a clinical diagnosis, i.e. as a pathologist one does not diagnose it.[19]

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Abbreviated NAFLD.

- Fatty liver that is not due to alcohol; includes obesity-related fatty liver, metabolic disease/diabetes-related fatty liver.

NASH

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis - see steatohepatitis section.

- Histologically indistinguishable from ASH.

- NASH is a clinical diagnosis based on exclusion of alcohol.

Steatohepatitis

Autoimmune

Autoimmune hepatitis

- Abbreviated AIH.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Abbreviated PBC.

Autoimmune hepatitis with obstruction - combined changes

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

Patient with SLE and obstructive jaundice that resolved with apparent passage of stone. A. Low power shows inflammation; portal triads, lobules, central veins cannot be distinguished. B. Trichrome shows central venous sclerosis (red arrowhead), periportal fibrosis (green arrowhead), & space of Disse collagenization (yellow arrowhead); juxtaposition of central vein & portal tract indicates collapse, no definite bridging was seen. C. Central vein is inflamed with a rare plasma cell (cyan arrowhead). D. Interface hepatitis with plasma cells (yellow arrows) and ballooned hepatocytes (red arrows). Lobule is disorganized. E. Proliferating bile ductules (blue arrows) with occasional neutrophils (fucsia arrows), indicative of obstruction, but not acute cholangitis, which requires inflamed bile duct itself, best diagnosed with associated blood vessel. F. Rare distorted rosettes with greenish brown strands of bile (left arrow) or bile plugs (right arrow).

Autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome

- Abbreviation AIH-PBC OS.

General

Epidemiology:

- Rare.

Serology:[20]

- AMA +ve.

- Anti-dsDNA +ve.

Microscopic

A.

B.

C.

D.

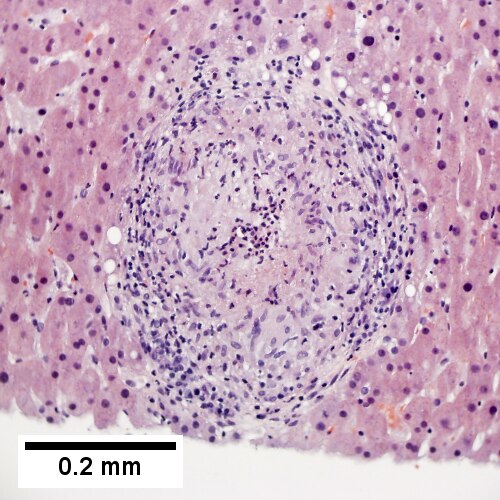

AIH/PBC overlap. AMA & ANA positive with Alkaline phosphatase > 2 upper limit of normal & one ALT > 5 times upper limit of normal. A. Expanded portal tracts with fuzzy edges. B. Interface hepatitis with plasma cells. C. Loose granuloma. D. Damaged bile duct.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Abbreviated PSC.

Hereditary

Caroli disease

General

- Genetic disease.

- Frequently associated with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD).[21]

- May be seen in isolation.[22]

Clinical:[23]

- Recurrent cholangitis.

- Recurrent cholelithiasis.

- Cholangiocarcinoma[24] - seen in ~7% of cases.[25]

Note:

- Caroli syndrome = Caroli disease + congenital hepatic fibrosis.[26]

Gross

- Dilated bile ducts.[21]

Microscopic

Features:[23]

- Dilated bile ducts.

- Periductal fibrosis. (???)

- +/-Fibrosis.

Image:

Hereditary hemochromatosis

- For secondary causes see secondary hemochromatosis.

Wilson disease

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- AKA alpha1-antiprotease inhibitor deficiency.

Other

Primary Systemic Sclerosis

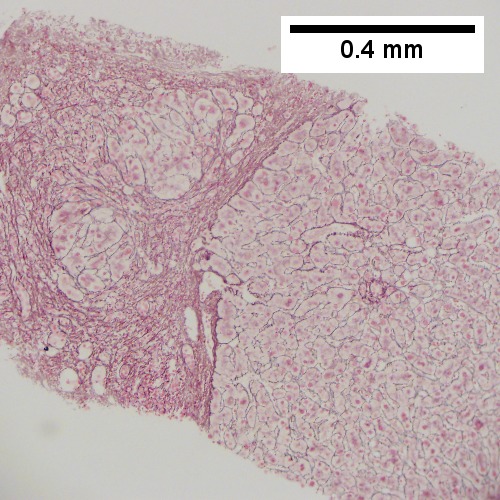

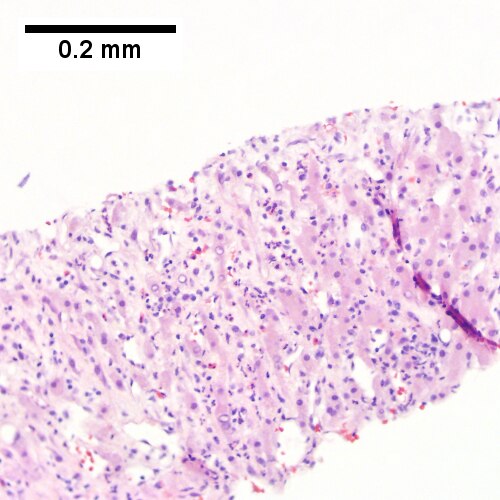

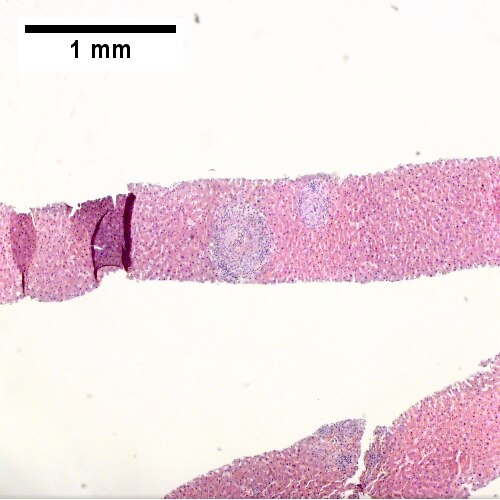

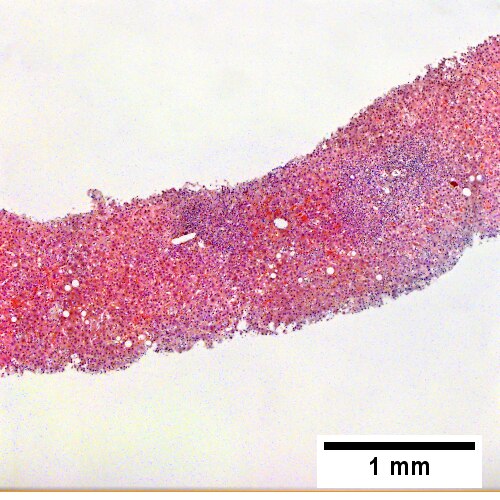

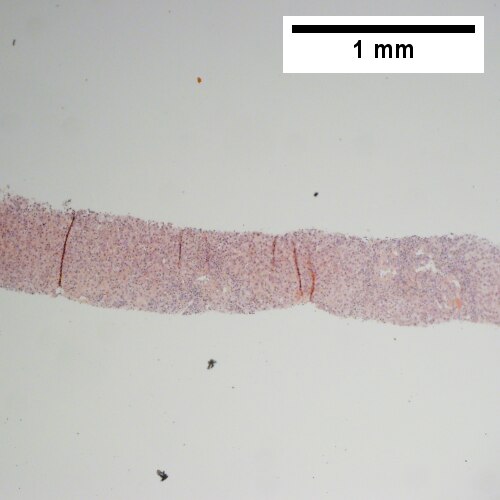

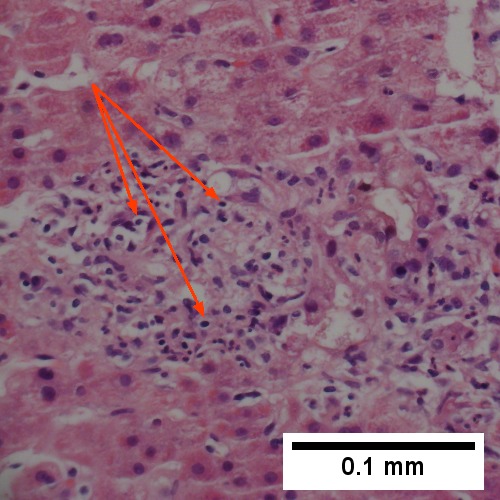

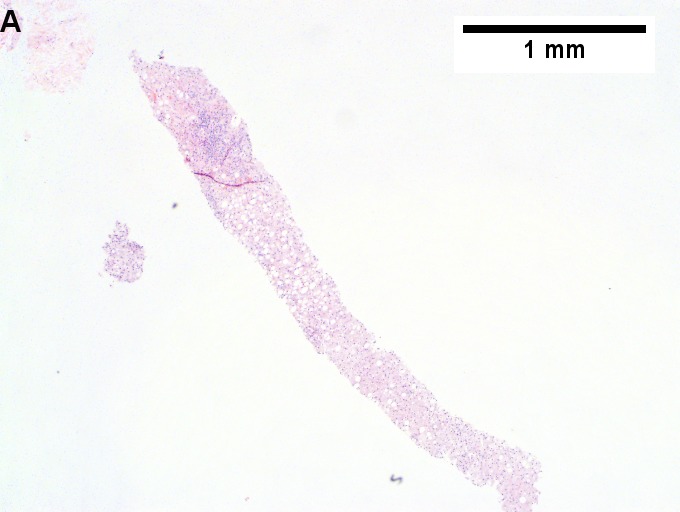

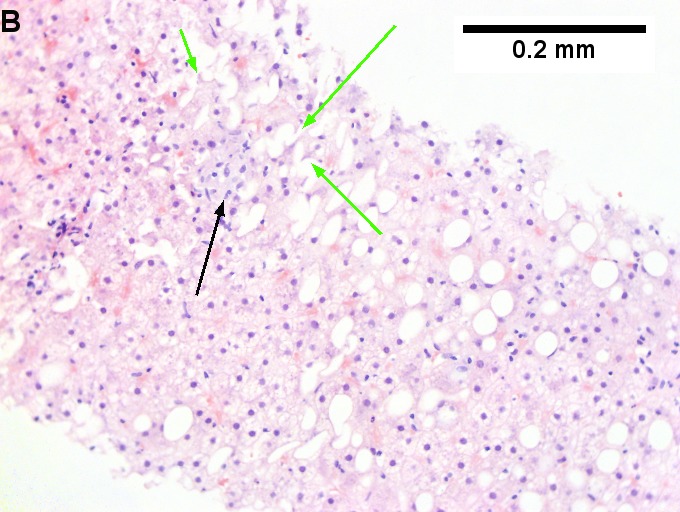

Primary systemic sclerosis in a 67 year old White, non-Hispanic man who had undergone renal transplantation for idiopathic nodular glomerusclerosis, which had recurred in 2013. He had been scheduled to receive a second transplantation, but had not yet received one. The patient had a positive anti-nuclear antigen study, with a positive scleroderma antibody (SCL-70), a high SCL-70 antibody index of 3.9, and negative DNA, Chromatin, Anti-Riboscomal P, SS-A, SS-B, anti Smith, RNP, JO-1, anticentromere antibody and rheumatoid factor serologic studies. Hepatitis A, B, and C serologic studies were negative. Liver function tests showed normal albumin and total bilirubin levels with alkaline phosphatase of 712 IU/L (35-129 normal range), alanine aminotransferase 59 IU/L (5-41 normal range), and aspartate aminotransferase 68 IU/L (5-37 normal range). This case provisions many of the features known to be present in primary systemic sclerosis as seen in the skin. A. At low power, triads appear almost as white ghosts against a relatively normal set of hepatocyte lobules. B. Closer examination reveals some triads to be expanded, with peripheral bile ductular proliferation and modest associated chronic inflammation without interface hepatitis. C. Portal arterioles had thick walls; inflammation included lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells. D. Trichrome failed to stain the material in the triads blue, but did show space of Disse collagenization. E. PAS with diastase showed positive staining of the material with emphasis on the arteriole walls. F. Hemosiderosis was seen on iron stain.

Budd-Chiari syndrome

- AKA hepatic vein obstruction.

General

- Hepatic outflow obstruction.

Clinical triad:[28]

- Ascites.

- Abdominal pain.

- Hepatomegaly.

Etiology:

- ~50% have a myeloproliferative disease.[29]

- May be due to mass effect from a tumour.

Clinical DDx:

Microscopic

Features:[30]

- Sinusoidal dilation in zone III (congestion).

- +/-Hepatocyte drop-out.

- +/-Centrilobular fibrosis.

DDx congestion:

- Congestive heart failure (congestive hepatopathy).

- Constrictive pericarditis.

Vanishing bile duct syndrome

General

- Fatal.

DDx:[32]

- Primary biliary cirrhosis.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

- GVHD.[33]

- Drugs.[34]

- Chronic rejection.[31]

Microscopic

Features:[32]

- Loss of intrahepatitic bile ducts - key feature.

- Cholestasis.

Note:

- May occur without fibrosis and inflammation; thus, can be easy to miss.

IHC

- CK7 -ve.

- Marks bile ducts.

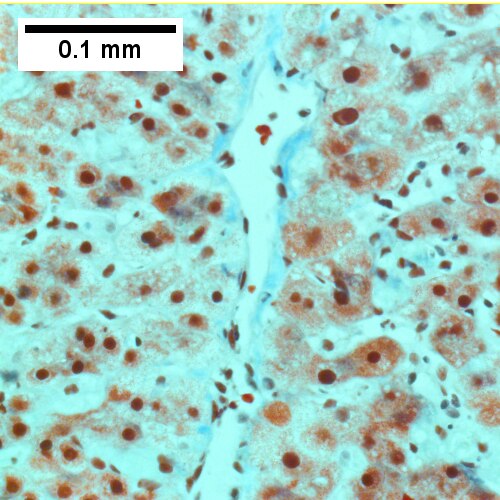

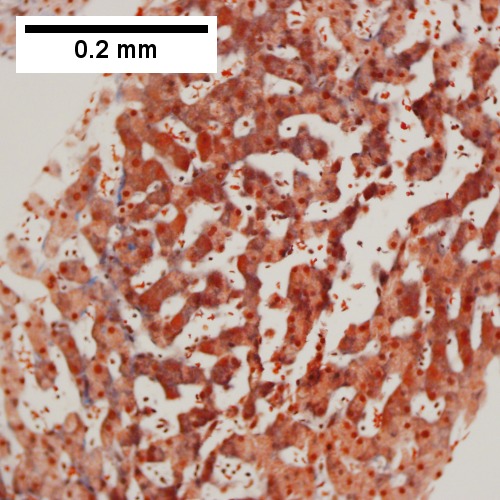

Hepatic Graft versus Host Disease (L-GVHD)

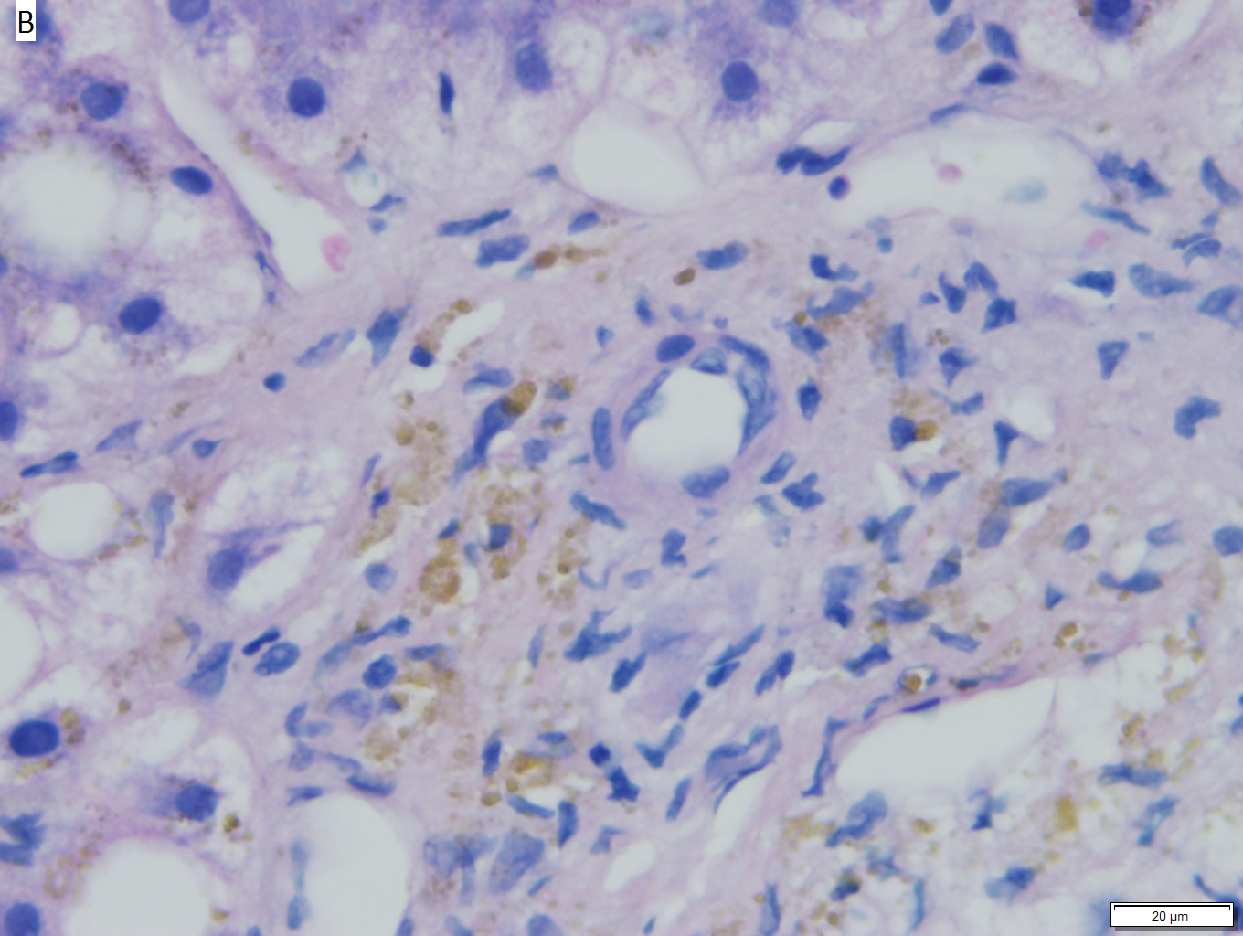

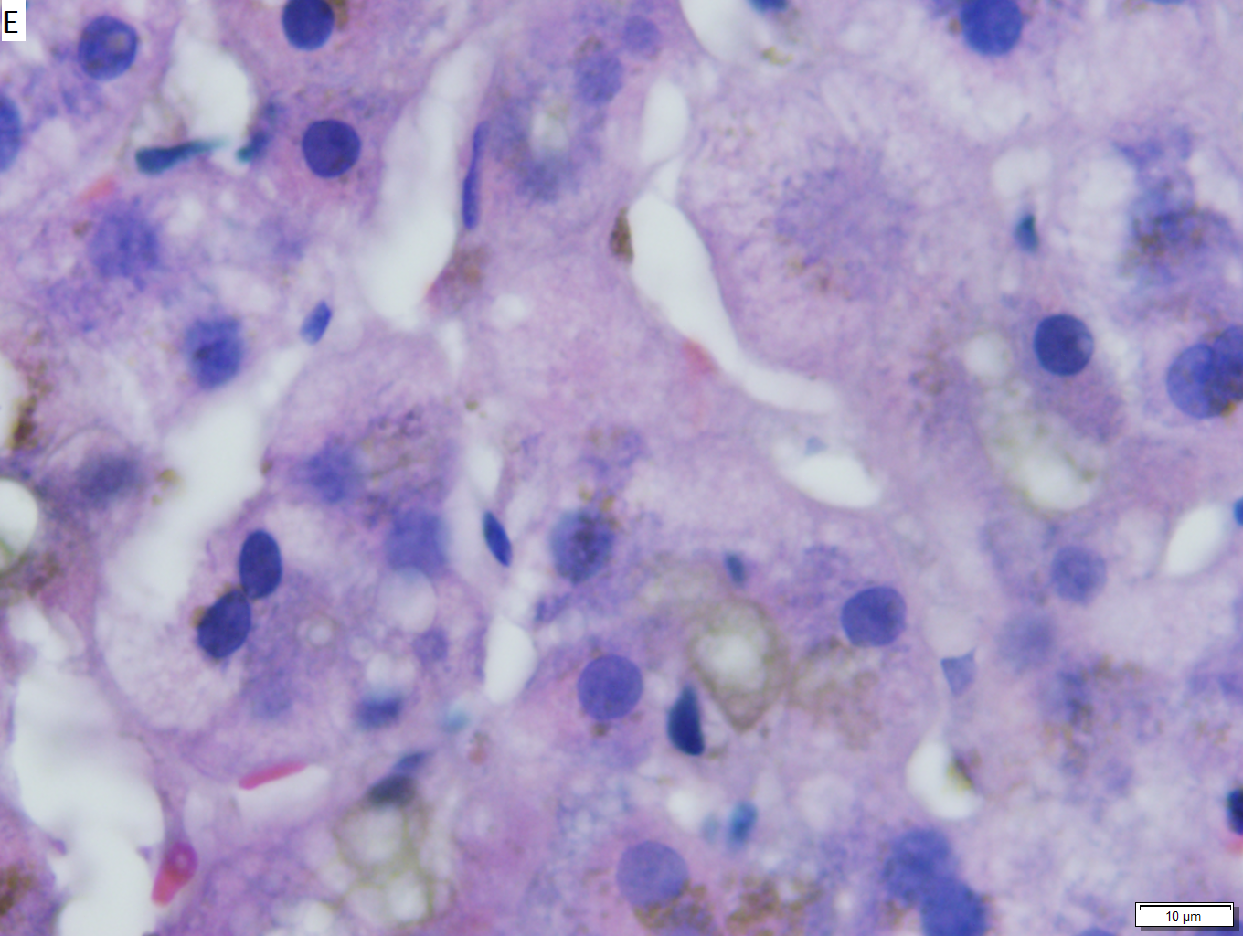

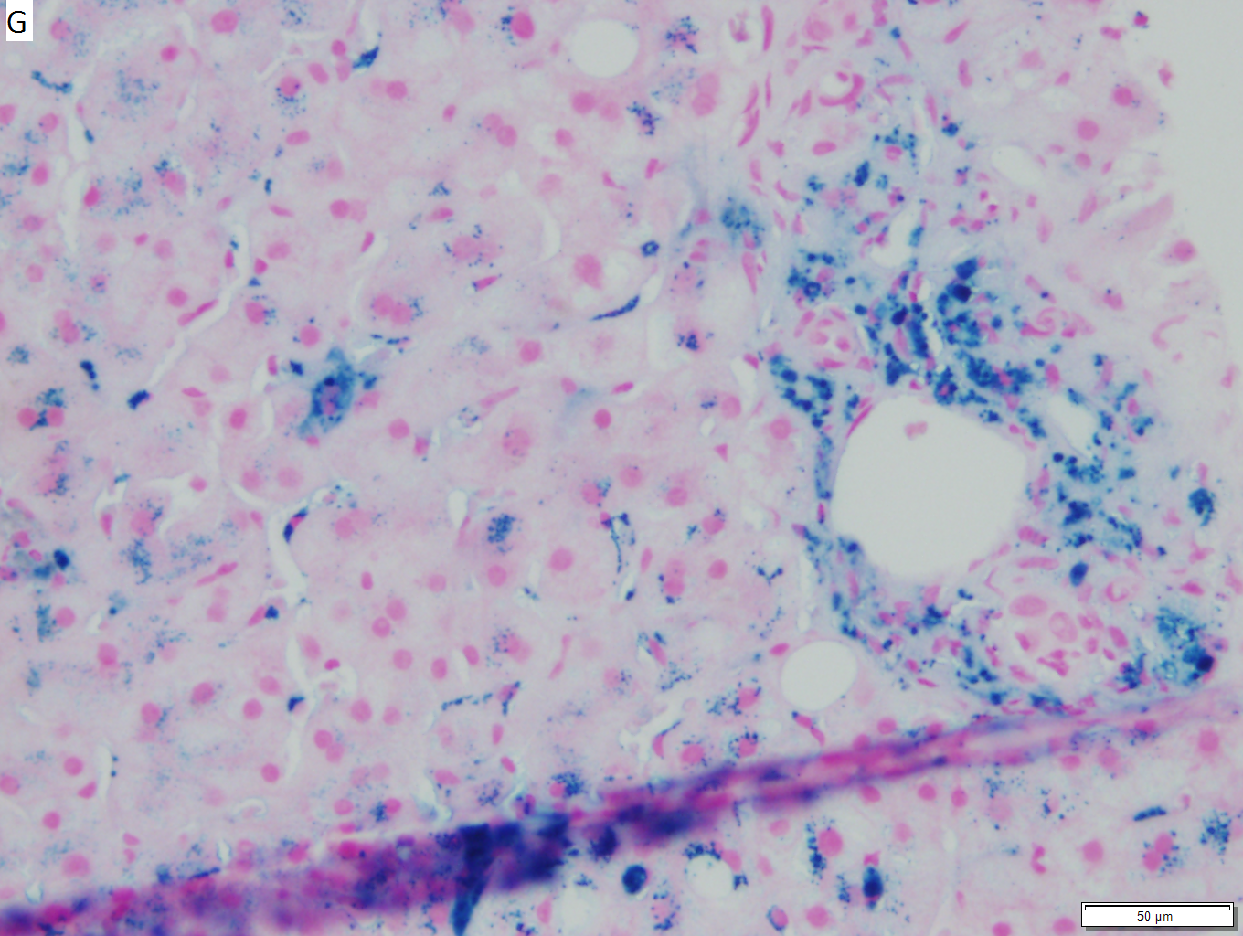

Hepatic graft versus host disease (L-GVHD) in a 22 yo man who underwent bone marrow transplantation after developing ALL. A. Low power view shows brownish discoloration in triad, but is otherwise of little interest. B. Arterioles in triads were accompanied by bile ducts in only 30% of cases; this image shows an arteriole without a bile duct. Note the pigment and the accompanying macrophage/lymphocyte inflammation, not extreme. The added chronic inflammation is a feature of chronic L-GVHD. C. Bile ducts, when shown, showed extensive damage, here seen as loss of cytoplasm, and nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia (other degenerative changes, not seen here, include nuclear dropout or necrosis, cytoplasmic eosinophilia, loss of duct lumen). Lymphocytosis into the ducts was not seen. D. Ballooned hepatocytes and dilated canaliculi were seen. E. Pigment was present, but mostly in Kupffer cells, not hepatocytes or as bile plugs. F. Up to two foci of spotty necrosis were seen in a 100X field (field shown is 200X); not shown are rare apoptotic hepatocytes. G. An iron stain showed the pigment represented extemsive iron deposition, with emphasis on Kupffer cells and portal triad macrophages, frustrating definite assessment of bile plugs in canaliculi. The hemosiderosis resulted from the many blood transfusions the patient had received.

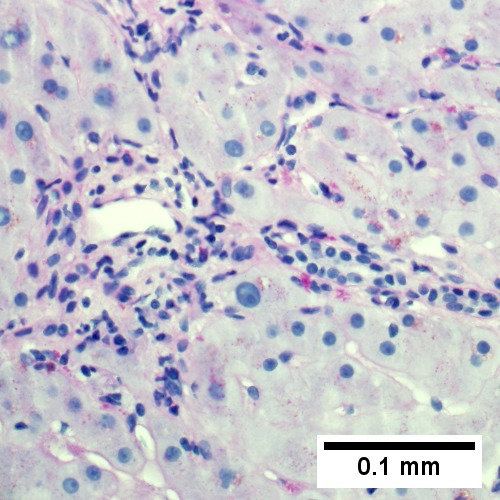

Extrahepatic biliary obstruction

A.

B. ![Bile in hepatocytes about central vein & in plugs in canaliculi [yellow arrowhead] (400X).](/w/images/thumb/0/00/2_OBS_3_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-2_OBS_3_680x512px.tif.jpg)

C.

D.

Early extrahepatic biliary obstruction, demonstrated radiographically, transient, with rise in bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases. Pure canalicular cholestasis near terminal hepatic venules also seen in acute hepatitis, drug reactions, benign recurrent cholestasis, pregnancy, sepsis, & lymphomas. A. Sinusoidal dilatation, circular spaces of hepatocytes, small portal triads. B. Bile in hepatocytes about central vein & in plugs in canaliculi [yellow arrowhead]. C. Trichrome shows fibrosis about central vein. D. PAS with diastase shows portal triads with mild edema and chronic inflammation, without tortuous bile duct.

A.

B. ![Edematous stroma, proliferating ductules [yellow arrowheads], PAS-D macrophages [red arrowhead] (PAS with diastasse, 200X)](/w/images/thumb/d/de/2_OBS_2_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-2_OBS_2_680x512px.tif.jpg)

C. ![Disordered, often swollen hepatocytes,some with feathery degeneration (net like spaces in cytoplasm [blue arrowhead], rare Councilman body [green arrowhead] (400X)](/w/images/thumb/d/d6/3_OBS_2_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-3_OBS_2_680x512px.tif.jpg)

D. ![Bile in hepatocytes [cyan arrrowhead] & in canaliculi [purple arrowheads]. Empty acinar spaces bounded by hepatocytes [orange arrowhead] (400X, higher pixel),](/w/images/thumb/2/2e/4_OBS_2_1360x1024px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-4_OBS_2_1360x1024px.tif.jpg)

Changes of extrahepatic biliary obstruction, months duration. A. Expanded inflamed portal triads, swollen hepatocytes. B. Edematous stroma, proliferating ductules [yellow arrowheads], PAS-D macrophages [red arrowhead]. C. Disordered, often swollen hepatocytes,some with feathery degeneration (net like spaces in cytoplasm) [blue arrowhead], rare Councilman body [green arrowhead]. D. Bile in hepatocytes [cyan arrrowhead] & in canaliculi [purple arrowheads]. Empty acinar spaces bounded by hepatocytes [orange arrowhead].

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

Large bile duct obstruction. A. Expanded, light colored portal triads (arrows). B. Proliferating bile ductules (cyan arrows) with neutrophils (yellow arrows), not specific for acute cholangitis, of assistance with large bile duct obstruction. C. Uninflamed interlobular duct (yellow arrow) with, accompanying blood vessel (red arrow). D. Bile infarct with pyknotic nuclei (arrows). E. Bile (arrow) in interlobular bile duct with disordered nuclei. F. Bile plugs in cannaliculi (red arrows), feathery degeneration producing foamy macrophage-like hepatocytes (yellow arrows).

Congestive hepatopathy

Drug-induced liver disease

- AKA drug-induced liver toxicity.

Focal nodular hyperplasia

- Abbreviated FNH.

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

General

- Associated with renal transplants, bone marrow transplants and vasculitides.[35]

- Can lead to portal hypertension and many of the associated complications.[36]

Etiology

- Arterial hypervascularity secondary to loss of hepatic vein radicles (loss of central venule in hepatic lobule).[35]

ASIDE: radicle = ramulus - smallest branch or vessel or nerve.[37]

Gross

- Diffuse nodularity - whole liver.

Microscopic

Features:[35]

- "Plump" hepatocytes surrounded by atrophic ones.

- No fibrosis.

Sinuosoidal obstruction syndrome

- May be referred to as Hepatic veno-occlusive disease.[38]

General

Clinical DDx:

Microscopic

Features:[30]

- Subendothelial swelling in hepatic venules.

Negatives:

- No thrombosis.

Ascending Cholangitis (Acute Cholangitis)

General

- Term for infection of bile ducts, usually due to obstruction

Clinical DDx:

Microscopic

Images

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

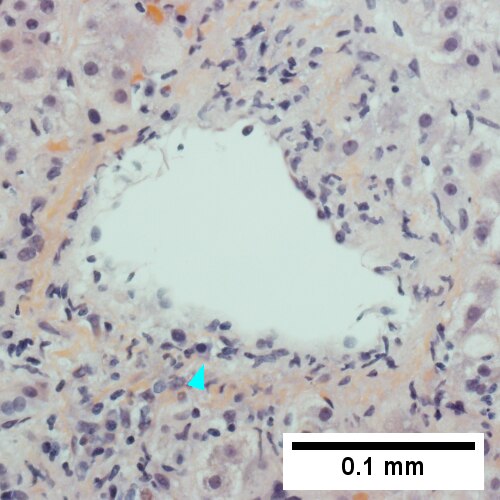

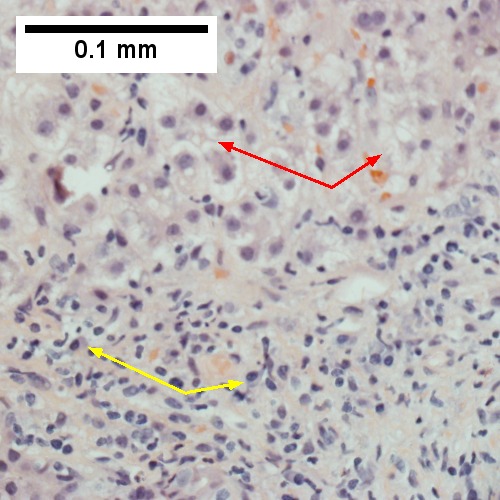

Acute cholangitis in a patient with multiple bile duct procedures. After the biopsy, removal of bile duct stones released pus. A. Rounded, clear (edematous) portal tracts (arrows) separated by hepatocytes with dilated sinusoids. B. Neutrophils about hepatocytes (arrows) have spilled into the lobule from a portal tract. C, Proliferated bile ductules (arrows) bearing neutrophils within epithelium and lumens are features of obstruction that should prompt a search for interlobular ducts with acute inflammation. D. The epithelium of the ducts can be severely degenerated. Neutrophils (cyan arrows) invade epithelium of an interlobular duct that are recognizable mainly as a circle of rounded nuclei; the associated arteriole (red arrow) should be identified to ensure an interlobular duct is being evaluated. Note the proliferated bile ductules (blue arrows). E. A PAS without diastase stain colors the arteriole (blue arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow). F. A PAS with diastase stain colors the arteriole (red arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow).

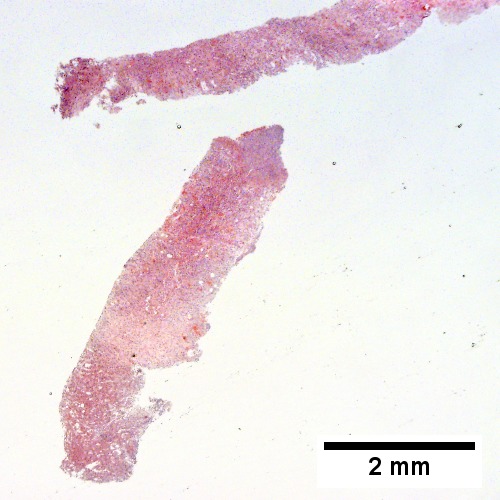

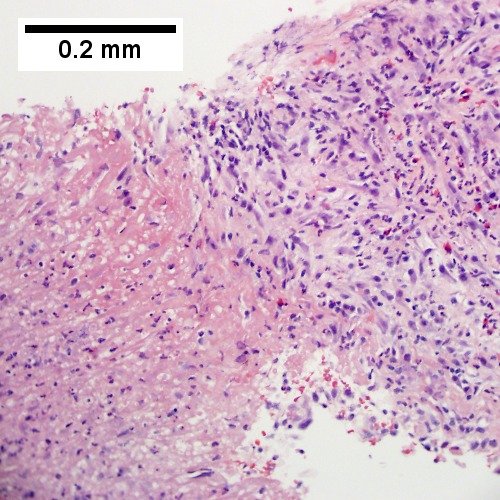

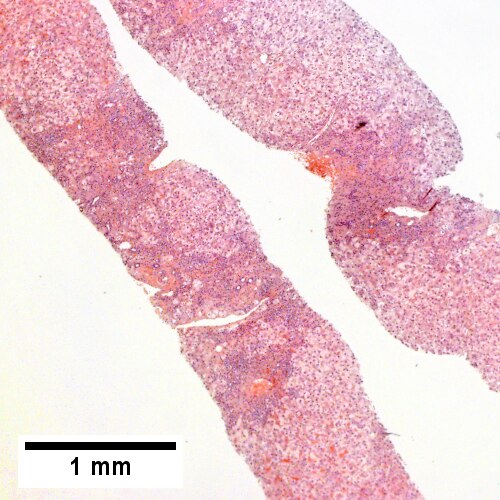

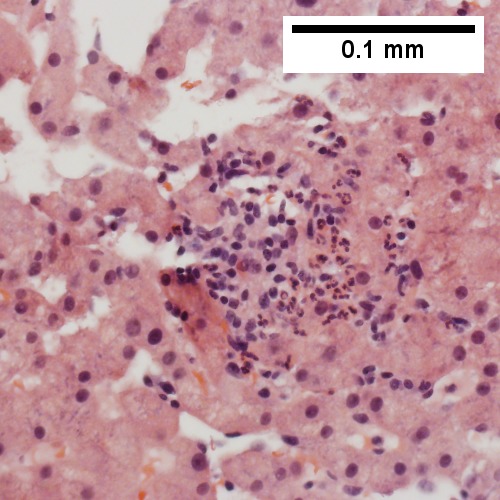

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

Patient with sepsis and acute cholangitis. A. Low power shows variably sized inflamed portal tracts. B. Trichrome shows dilated sinusoids and space of Disse collagenization. C. Inflammatory focus with macrophages and neutrophils. D. PAS with diastase shows proliferated bile ductules at edge of triad with neutrophils, which should not be used to make a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis. E. PAS without diastase showing acutely inflamed bile duct, with accompanying blood vessel of similar size, diagnostic of acute cholangitis. F. PAS with diastase showing neutrophil in bille duct lumen, diagnostic of acute cholangitis.

Polycystic kidney disease and the liver

General

Complications of PKD in the liver:[40]

- Infected cyst.

- Cholangiocarcinoma.

- Cholestasis/obstruction due to duct compression.[41]

Cysts:

- Cysts in the liver, like the kidney, are thought to enlarge with age.

Microscopic

Features:[42]

- Von Meyenburg complexes (bile duct hamartoma):

- Cluster of dilated ducts with "altered" bile.

- Surrounded by collagenous stroma.

- Separate from the portal areas.[43]

Images:

Notes:

Peliosis hepatis

Total parenteral nutrition

- Abbreviated TPN.

General

- Indication: short gut syndrome, others.

Microscopic

Variable - may range from: steatosis, steatohepatitis, cholestasis, fibrosis and cirrhosis.[46]

- Steatosis (periportal) - early.

- Cholestasis - late.

Giant cell hepatitis

- AKA neonatal giant cell hepatitis.

- See: Giant cell hepatitis.

Hepatic amyloidosis

General

- Diffuse abundant amyloid within the space of Disse is associated with portal hypertension.[8]

Microscopic

Features:

- Amorphous extracellular pink stuff on H&E - see amyloid article.

DDx:

Images

A. ![Amorphous material replaces hepatic parenchyma [4X]](/w/images/thumb/2/28/1_AMY_1_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-1_AMY_1_680x512px.tif.jpg)

B. ![Material barely stains blue on trichrome [10X]](/w/images/thumb/8/8a/2_AMY_1_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-2_AMY_1_680x512px.tif.jpg)

C. ![Material stains red on unpolarized Congo Red [40X]](/w/images/thumb/6/6a/3_AMY_1_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-3_AMY_1_680x512px.tif.jpg)

D. ![Material stains apple green on polarized Congo Red [40X]](/w/images/thumb/2/22/4_AMY_1_680x512px.tif/lossy-page1-500px-4_AMY_1_680x512px.tif.jpg)

Amyloidosis. A. Amorphous material replaces hepatic parenchyma. B. Material barely stains blue on trichrome. C. Material stains red on unpolarized Congo Red. D. Material stains apple green on polarized Congo Red.

Stains

- Congo red +ve.

Fulminant hepatic necrosis

Secondary hemochromatosis

- For the hereditary one see hereditary hemochromatosis.

General

- Iron overload secondary to blood transfusions for hereditary or acquired anemia.[49]

- Primary hemochromatosis due to a defect in iron processing - called hereditary hemochromatosis.

- Imaging considered the best test, as iron deposition is patchy.[49]

Selected hereditary causes:[49]

- Thalassemia.

- Sickle cell anemia.

- Hereditary sideroblastic anemia.

Selected acquired causes:[49]

- Myelodysplastic syndromes

- Myelofibrosis

- Aplastic anemia, intractable.

Microscopic

Hepatic sarcoidosis

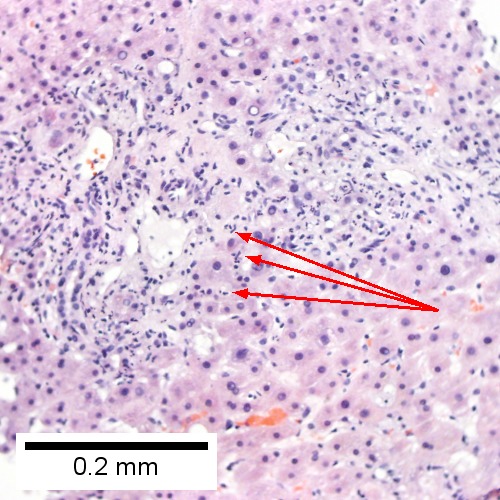

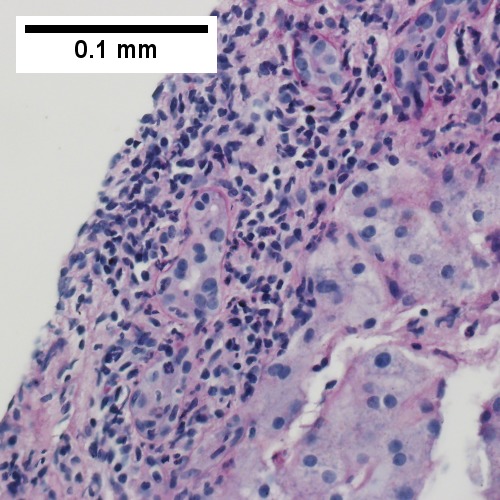

Overlapping Disorders

Changes of steatohepatitis and interface hepatitis, with granuloma. Patient with diabetes was ANA, AMA, HCV, HBV negative, without drugs known to produce granulomas or interface hepatitis. This may be a case of AMA negative primary biliary cirrhosis, but studies to determine that with certainty were not performed. A. Low power shows hepatocytes afflicted by steatosis and an inflamed portal tract. B. In a region of fatty change lie cytoplasmic tufts of ballooning degeneration (green arrows) and a lipogranuloma (black arrow). C. At the portal-hepatocyte junction lies interface hepatitis (black arrows), as well as extension of inflammation into the lobule (green arrows). D. Red hepatocytes bounded by inflammation denote piecemeal necrosis [PAS without diastase]. E. Giant cells intermixed with lymphocytes prove a portal granuloma [PAS without diastase]. F. A blue fibrous bridge extends from a triad [Trichrome].

Acute obstructive changes and changes of recurrent injury in 46 yo man with Clostridium perfringens positive blood culture, an ERCP that showed duodenal compression by the pancreas with resultant bile duct dilatation. The patient had had and continued to have multiple bouts of acute pancreatitis. At the time of biopsy, decreased platelet count/hemoglobin/albumin, elevated lipase/amylase/PT/PTT, normal alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, AST/ALT, AMA, hepatitis virus serology, ANA. A. Fragment biopsy shows inflamed triads and bridges. B. Trichrome shows bridges without nodules, evidence of prior injury; the patient subsequently developed multiple episodes of pancreatitis. C. Reticulin shows piecemeal necrosis, with black lines bounding individual hepatocytes at interface (arrows). D. Collapse is shown by closly approximated thick black lines; one cannot call portal-central collapse without seeing a central vein. Note on this and the other reticulin image that regeneration, two cell thick cords, is not prominent. E. PAS D of two portal triads, far nearer than normal, both expanded. Note increased number of ducts/ductules (red arrows), neutrophils, and PAS-D macrophages. F. PAS D shows collapse extending from a triad to a portion of a lobule with steatosis. No feathery degeneration or bile duct plugs were seen. Neither were foci of spotty necrosis or abscess seen. G. Other triads, again edematous, showed more of a chronic inflammatory response, with occasional plasma cells (black arrows). Also present are neutrophils (red arrows). The bile duct (grey arrow) near the artery (brown arrow) shows mildly disturbed nuclei. Note early proliferated bile ductules (cyan arrows).

Hepatitis B virus with steatohepatitis in a 36 year old man with hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis Be antigen positivity, Hepatitis be QTPC of 1750 cop/mL, an occasionally mildly elevated (42) ALT, and normal glucose, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and other transaminases. He had a history of alcohol abuse, which became controlled. A. Triads show scant inflammation without definite interface hepatitis. About one-fourth of the lobule, not pan-acinar, is afflicted by steatosis. B. Occasional tufts are seen (arrow), indicating focal ballooning sufficient for a diagnosis of steatohepatitis. C. Glycogenated nuclei (black arrows) and hepatocytes with feathery degeneration (red arrows) are seen. D. Very rare foci of spotty necrosis were seen. E. Apart from this triad and the one in the trichrome stain in F, which had moderate inflammation comprising lymphocytes and macrophages, all triads were small, most without any inflammation at all. Neither collapse nor piecemeal necrosis were seen on reticulin stain. F. Trichrome stain showed only portal fibrosis. The interhepatocyte fibrosis required for brunt fibrosis stage I was not seen. Hence, one would grade this as follows: A) Chronic hepatitis (history of hepatitis B), Metavir activity index 1, Piecemeal necrosis 0, Lobular necrosis 1, Metavir fibrosis stage 1, B) Steatohepaitits, Brunt necroinflammatory grade 1, Brunt fibrosis stage 0.

See also

References

- ↑ Mitchell, Richard; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon (2011). Pocket Companion to Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 448. ISBN 978-1416054542.

- ↑ Mitchell, Richard; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon (2011). Pocket Companion to Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 441. ISBN 978-1416054542.

- ↑ URL: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/hepatology/hepatitis-B/. Accessed on: 16 May 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 URL: http://www.labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/hepatitis_b/test.html. Accessed on: 16 May 2011.

- ↑ URL: http://labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/hepatitis-b/tab/test. Accessed on: 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Diagnostic accuracy of serum ceruloplasmin in Wilson disease: determination of sensitivity and specificity by ROC curve analysis among ATP7B-genotyped subjects. Mak CM, Lam CW, Tam S. Clin Chem. 2008 Aug;54(8):1356-62. Epub 2008 Jun 12. PMID 18556333. URL: http://www.clinchem.org/cgi/reprint/54/8/1356.pdf. Accessed on: 28 September 2009.

- ↑ URL: http://insidesurgery.com/2010/12/hepatopedal-hepatofugal-flow/. Accessed on: 2 December 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bion, E.; Brenard, R.; Pariente, EA.; Lebrec, D.; Degott, C.; Maitre, F.; Benhamou, JP. (Feb 1991). "Sinusoidal portal hypertension in hepatic amyloidosis.". Gut 32 (2): 227-30. PMC 1378815. PMID 1864548. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1378815/.

- ↑ Burt, Alastair D.;Portmann, Bernard C.;Ferrell, Linda D. (2006). MacSween's Pathology of the Liver (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 418. ISBN 978-0-443-10012-3.

- ↑ OA. September 2009.

- ↑ "Terminology of chronic hepatitis, hepatic allograft rejection, and nodular lesions of the liver: summary of recommendations developed by an international working party, supported by the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Los Angeles, 1994.". Am J Gastroenterol 89 (8 Suppl): S177-81. Aug 1994. PMID 8048409.

- ↑ URL: http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/hepatitis-b.html. Accessed on: 2 May 2012.

- ↑ Jeong SH, Lee HS (2010). "Hepatitis A: clinical manifestations and management". Intervirology 53 (1): 15–9. doi:10.1159/000252779. PMID 20068336.

- ↑ Mitchell, Richard; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon (2011). Pocket Companion to Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 448. ISBN 978-1416054542.

- ↑ URL: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/170539-overview. Accessed on: 3 May 2012.

- ↑ STC. 6 December 2010.

- ↑ STC. 6 December 2010.

- ↑ Jensen K, Gluud C (November 1994). "The Mallory body: theories on development and pathological significance (Part 2 of a literature survey)". Hepatology 20 (5): 1330-42. PMID 7927269.

- ↑ MG. September 2009.

- ↑ Muratori, P.; Granito, A.; Pappas, G.; Pendino, GM.; Quarneti, C.; Cicola, R.; Menichella, R.; Ferri, S. et al. (Jun 2009). "The serological profile of the autoimmune hepatitis/primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome.". Am J Gastroenterol 104 (6): 1420-5. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.126. PMID 19491855.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 263200

- ↑ Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 600643

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Yonem, O.; Bayraktar, Y. (Apr 2007). "Clinical characteristics of Caroli's syndrome.". World J Gastroenterol 13 (13): 1934-7. PMID 17461493.

- ↑ Yonem, O.; Bayraktar, Y. (Apr 2007). "Clinical characteristics of Caroli's disease.". World J Gastroenterol 13 (13): 1930-3. PMID 17461492.

- ↑ Karim, AS. (Aug 2004). "Caroli's disease.". Indian Pediatr 41 (8): 848-50. PMID 15347876.

- ↑ Brancatelli, G.; Federle, MP.; Vilgrain, V.; Vullierme, MP.; Marin, D.; Lagalla, R.. "Fibropolycystic liver disease: CT and MR imaging findings.". Radiographics 25 (3): 659-70. doi:10.1148/rg.253045114. PMID 15888616.

- ↑ URL: http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedEd/orfpath/develop.htm. Accessed on: 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Fox, MA.; Fox, JA.; Davies, MH. (2011). "Budd-Chiari syndrome--a review of the diagnosis and management.". Acute Med 10 (1): 5-9. PMID 21573256.

- ↑ Plessier, A.; Valla, DC. (Aug 2008). "Budd-Chiari syndrome.". Semin Liver Dis 28 (3): 259-69. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1085094. PMID 18814079.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Aydinli, M.; Bayraktar, Y. (May 2007). "Budd-Chiari syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis.". World J Gastroenterol 13 (19): 2693-6. PMID 17569137. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i19/2693.htm.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Inomata, Y.; Tanaka, K. (2001). "Pathogenesis and treatment of bile duct loss after liver transplantation.". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 8 (4): 316-22. doi:10.1007/s0053410080316. PMID 11521176.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Reau, NS.; Jensen, DM. (Feb 2008). "Vanishing bile duct syndrome.". Clin Liver Dis 12 (1): 203-17, x. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2007.11.007. PMID 18242505.

- ↑ Yeh, KH.; Hsieh, HC.; Tang, JL.; Lin, MT.; Yang, CH.; Chen, YC. (Aug 1994). "Severe isolated acute hepatic graft-versus-host disease with vanishing bile duct syndrome.". Bone Marrow Transplant 14 (2): 319-21. PMID 7994249.

- ↑ Chitturi, S.; Farrell, GC. (Apr 2001). "Drug-induced cholestasis.". Semin Gastrointest Dis 12 (2): 113-24. PMID 11352118.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 922. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ Bissonnette, J.; Généreux, A.; Côté, J.; Nguyen, B.; Perreault, P.; Bouchard, L.; Pomier-Layrargues, G. (Aug 2012). "Hepatic hemodynamics in 24 patients with nodular regenerative hyperplasia and symptomatic portal hypertension.". J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27 (8): 1336-40. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07168.x. PMID 22554152.

- ↑ Dorland's Medical Dictionary. 30th Ed.

- ↑ DeLeve, LD.; Shulman, HM.; McDonald, GB. (Feb 2002). "Toxic injury to hepatic sinusoids: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (veno-occlusive disease).". Semin Liver Dis 22 (1): 27-42. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23204. PMID 11928077..

- ↑ Helmy, A. (Jan 2006). "Review article: updates in the pathogenesis and therapy of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.". Aliment Pharmacol Ther 23 (1): 11-25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02742.x. PMID 16393276.

- ↑ Burt, Alastair D.;Portmann, Bernard C.;Ferrell, Linda D. (2006). MacSween's Pathology of the Liver (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 174-5. ISBN 978-0-443-10012-3.

- ↑ URL: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=9184868. Accessed on: 23 September 2009.

- ↑ Burt, Alastair D.;Portmann, Bernard C.;Ferrell, Linda D. (2006). MacSween's Pathology of the Liver (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 176. ISBN 978-0-443-10012-3.

- ↑ Meyenburg complex. Stedman's Medical Dictionary. 27th Ed.

- ↑ Bile duct hamartomas--the von Meyenburg complex. Salles VJ, Marotta A, Netto JM, Speranzini MB, Martins MR. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007 Feb;6(1):108-9. PMID 17287178.

- ↑ [The von Meyenburg complex] Schwab SA, Bautz W, Uder M, Kuefner MA. Rontgenpraxis. 2008;56(6):241-4. German. PMID 19294869.

- ↑ Guglielmi FW, Boggio-Bertinet D, Federico A, et al. (September 2006). "Total parenteral nutrition-related gastroenterological complications". Dig Liver Dis 38 (9): 623–42. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.04.002. PMID 16766237.

- ↑ Li, SJ.; Nussbaum, MS.; McFadden, DW.; Gapen, CL.; Dayal, R.; Fischer, JE. (Aug 1988). "Addition of glucagon to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) prevents hepatic steatosis in rats.". Surgery 104 (2): 350-7. PMID 3135627.

- ↑ Stanko, RT.; Nathan, G.; Mendelow, H.; Adibi, SA. (Jan 1987). "Development of hepatic cholestasis and fibrosis in patients with massive loss of intestine supported by prolonged parenteral nutrition.". Gastroenterology 92 (1): 197-202. PMID 3096806.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Gattermann, N. (Jul 2009). "The treatment of secondary hemochromatosis.". Dtsch Arztebl Int 106 (30): 499-504, I. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0499. PMC 2735704. PMID 19727383. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2735704/.