Drug-induced liver disease

Drug-induced liver disease, also drug-induced liver toxicity and drug liver injury, is relatively common.

Drug reactions in general are dealt with in drug toxicity.

General

- Drugs can do almost anything; may include: granulomata, bile duct loss, cholestasis, ischemic type injury.

- Effects can be delayed -- temporal relationship not always obvious.

Microscopic

Features:

- Non-specific findings.

- +/-Eosinophils[1] - significant suggestive finding.

- +/-Steatosis - periportal macrovesicular, microvesicular.

- +/-Vanishing bile duct syndrome.

- +/-Granulomas.

Images

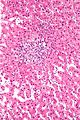

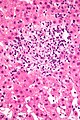

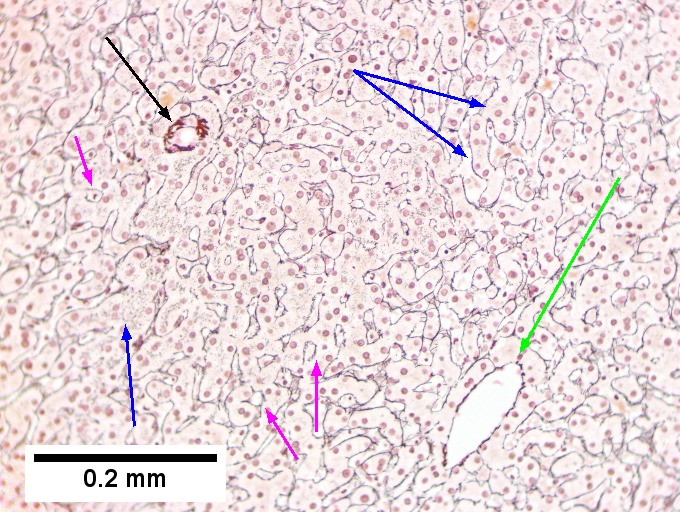

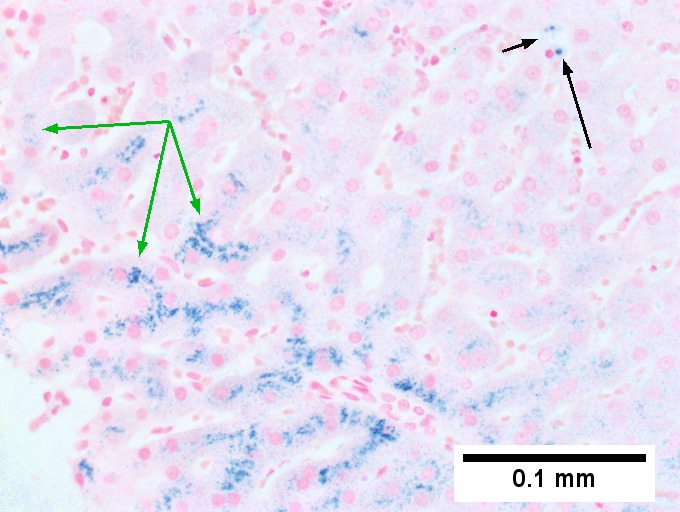

Hemochromatosis with DILI canalicular cholestasis with mild hepatocyte injury in the form of regeneration. This young adult man presented with jaundice; canalicular cholestasis was explicable on the basis of one or more of the medications he had been given. Iron positivity came as a surprise. Canalicular cholestasis, accumulation of bile in canaliculi, and, at times, choangioles, is most commonly seen with steroids. When damage to hepatocytes & portal inflammation accompanies canalicular cholestasis, drugs such as chlorpromazine and erythromycin, are most often responsible. Pure ductular cholestasis has been associated with benoxaprofen or sepsis. Cholangiodestructive (e.g., with destroyed bile ducts) cholestasis has been associated with paraquat, chlorpromazye, and other drugs. Some drugs, eg, phenytoin are also noted to be associated with mixed hepatocellular/cholestatic injury. Others have bile duct proliferation with eosinophils as a response.[1]

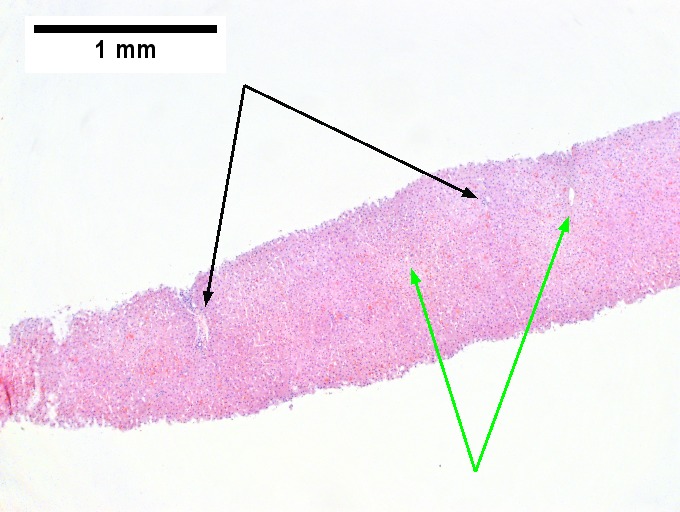

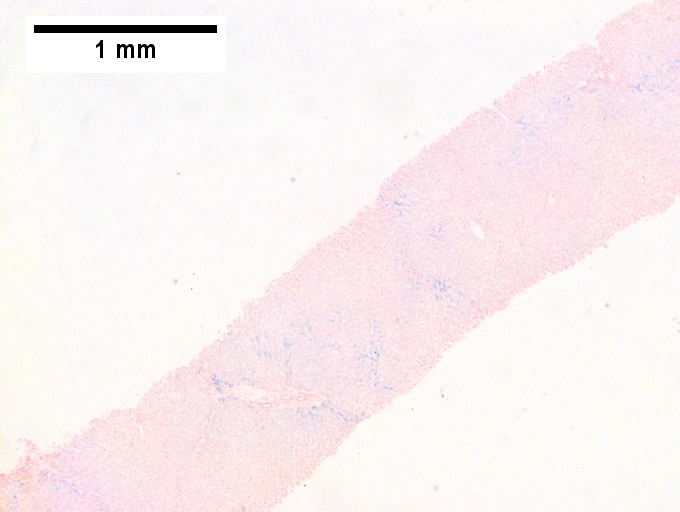

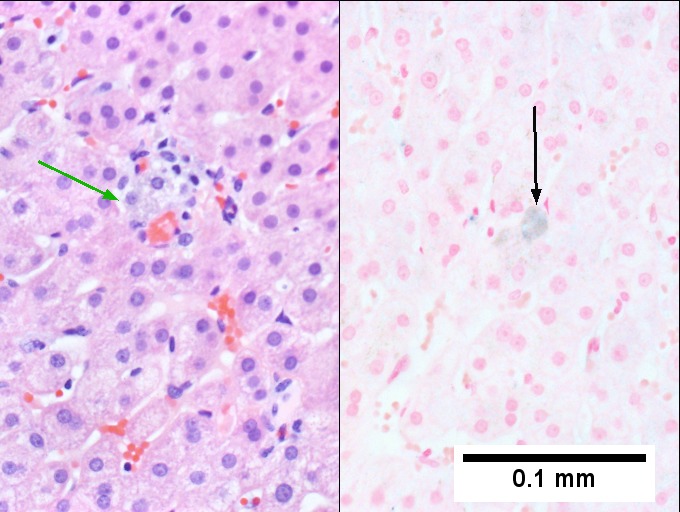

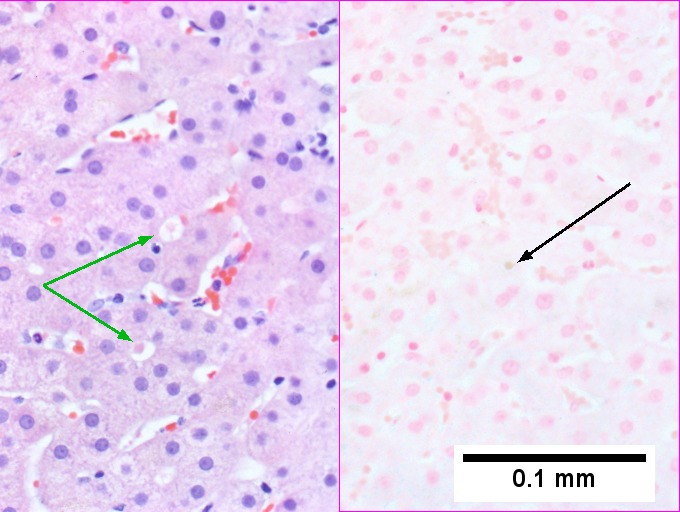

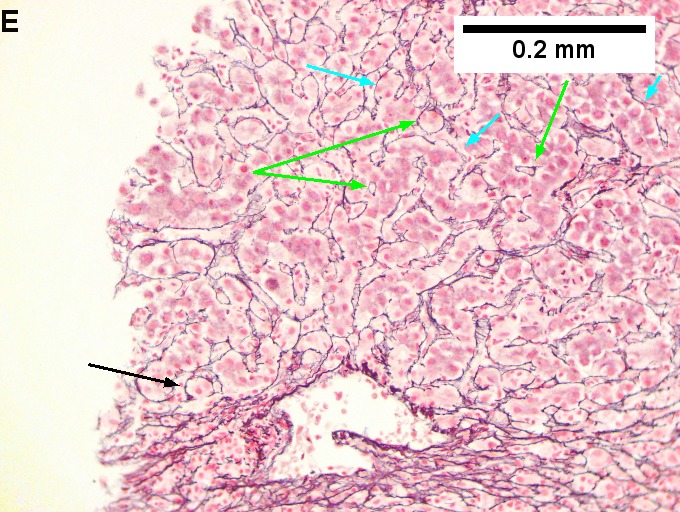

Present at low power are seemingly normal portal triads [black arrows], normal central veins [green arrows] and normal intervening parenchyma (Row 1 Left 40X). Iron stain shows 3+ iron deposition (Row 1 Right 40X). A reticulin stain shows changes of injury. Lines between portal triad [black arrow] and central vein [green arrow] lack directionality. Regeneration is seen in two-three hepatocyte cords [blue arrows] and hepatocyte rosettes [magenta arrows]; canaliculi are not highlighted by reticulin stain. (Row 2 Left 100X). Iron stain shows predominantly hepatocellular iron deposition [green arrows] with occasional Kupffer cell staining [black arrows] (Row 2 Right 400X). Distinguishing iron from bile can be accomplished by evaluating location of pigment. In pure canalicular cholestasis with mild hepatocyte injury, unusual are macrophages with bile staining in the lobule, being as they are confined to the sinusoids; the pigment on left on H&E in a sinusoidal macrophage [green arrow], stains blue on iron stain on similar macrophage [black arrow] (Row 3 Left 400X). Note the canalicular pigment on left on HE, [green arrows] ; a similar ball on the iron stain on the right lacks any stain [black arrow] (Row 3 Right 400X).

[1]H.J. Zimmerman, KG Ishak, “Hepatic injury due to drugs and toxins.” In Pathology of the Liver. RNM MacSween, et al, eds. New York: Churchill-Livingston. 2002: 638-641.

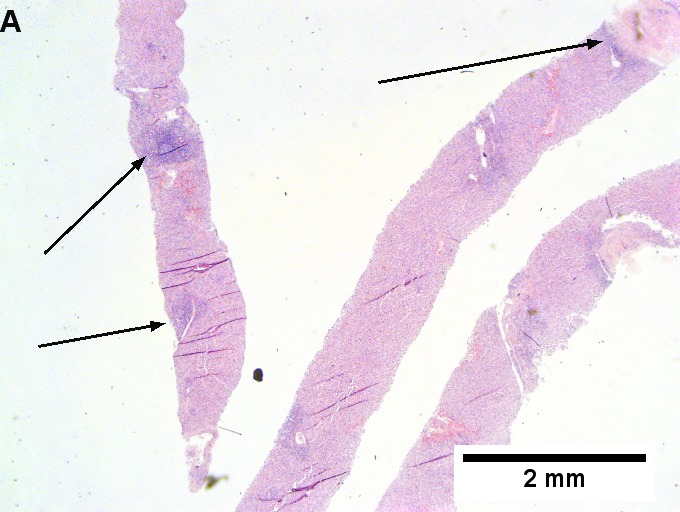

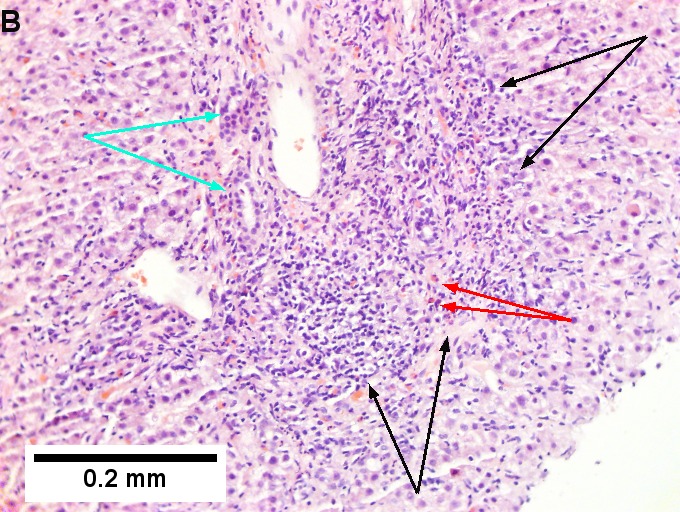

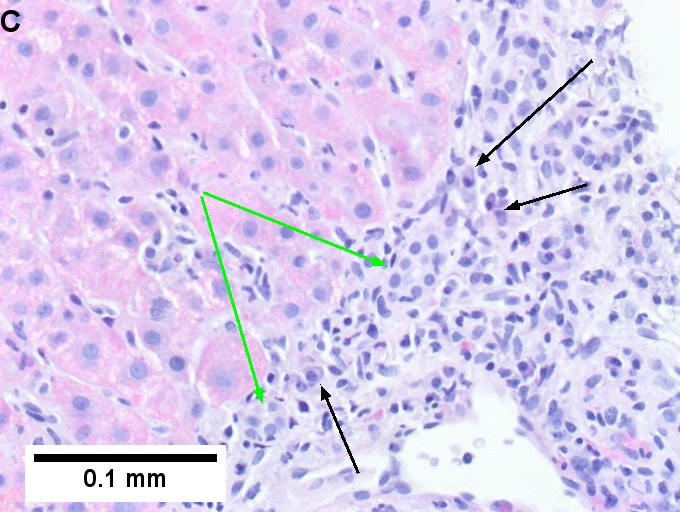

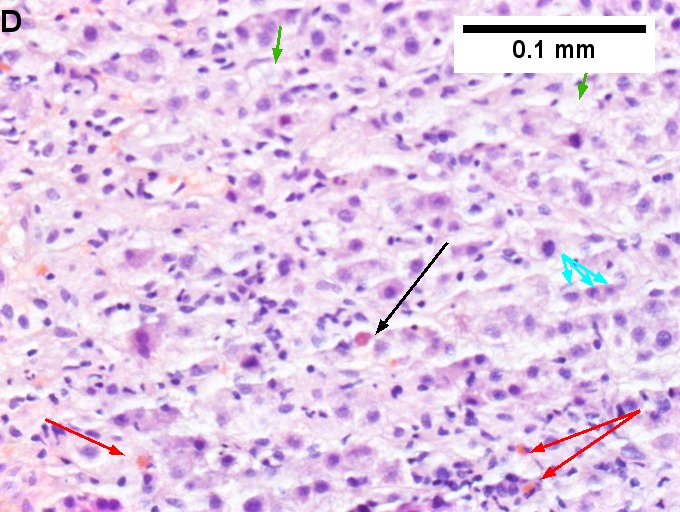

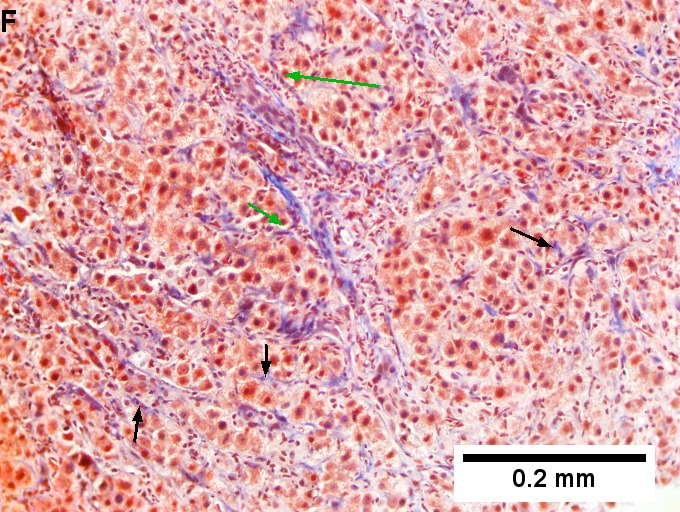

Drug induced liver injury in a young adult man. Acute onset hepatitis with albumin 3.2, ALT 1078, Alkaline phosphatase 141, direct bilirubin 6.3. A. Dark expanded triads (arrows) strew, at low power, normal hepatocyte lobules [20x]. B. A triad shows interface hepatitis (black arrows), a proliferated bile ductule (cyan arrows), and eosinophils (red arrows). [200X]. C. PAS without diastase highlights interface hepatitis with intact plate, lacking piecemeal necrosis, as well as the multiple plasma cells (arrows) and a proliferated bile ductule (green arrows) [400X]. D. Intense lobular inflammation, including eosinophils (red arrows) is associated with foamy cytoplasm of feathery degeneration in hepatocytes (green arrows), degenerated, small hepatocytes (cyan arrows), and a councilman body (black arrow) [400X]. F. Reticulin shows regeneration, with two cell thick cords (cyan arrows) and hepatocyte rosettes (green arrows), as well as a single cell with piecemeal necrosis (black arrow) [200X]. F. Trichrome shows perihepatocyte fibrosis (black arrows) and short fibrous spikes off triads (green arrows) [200X].

Specific patterns

Acute hepatits:

- Related to Rx - most often antibiotics.

- Amiodarone - cardiac arrhythmias.

- Tamoxifen - breast cancer.

- Carbamazepine - seizures.

- Venlafaxine - depression.[3]

- Thalidomide - multiple myeloma.[4]

Specific drugs

Acetaminophen:

- Zone 3 necrosis.

Methotrexate - chronic use:

- Histology:[7]

- Features of steatohepatitis.

- Zone III steatosis.

- Ballooning degeneration.

- Portal inflammation with mixed population (lymphocytes, macrophages, PMNs).

- Nuclear atypia (hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, vacuolation).

- Described as just nuclear size variation by some.[8]

- Features of steatohepatitis.

Sign out

LIVER, MEDICAL CORE BIOPSIES: - MILD STEATOHEPATITIS AND MILD FIBROSIS (1/4). - MILD TO MODERATE STEATOSIS. COMMENT: The findings are compatible with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) or drug effect. The steatosis is periportal predominant; this is not typical for NASH or ASH. Clinical correlation and review of medications is suggested.

See also

References

- ↑ Tadrous, Paul.J. Diagnostic Criteria Handbook in Histopathology: A Surgical Pathology Vade Mecum (1st ed.). Wiley. pp. 166. ISBN 978-0470519035.

- ↑ Grieco, A.; Forgione, A.; Miele, L.; Vero, V.; Greco, AV.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gasbarrini, G.. "Fatty liver and drugs.". Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 9 (5): 261-3. PMID 16237810.

- ↑ Stadlmann, S.; Portmann, S.; Tschopp, S.; Terracciano, LM. (Nov 2012). "Venlafaxine-induced cholestatic hepatitis: case report and review of literature.". Am J Surg Pathol 36 (11): 1724-8. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826af296. PMID 23073329.

- ↑ Vilas-Boas, F.; Gonçalves, R.; Sobrinho Simões, M.; Lopes, J.; Macedo, G. (Oct 2012). "Thalidomide-induced acute cholestatic hepatitis: case report and review of the literature.". Gastroenterol Hepatol 35 (8): 560-6. doi:10.1016/j.gastrohep.2012.05.007. PMID 22789729.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Millea PJ (August 2009). "N-acetylcysteine: multiple clinical applications". Am Fam Physician 80 (3): 265–9. PMID 19621836.

- ↑ URL: http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/69310.cfm. Accessed on: 19 October 2010.

- ↑ Burt, Alastair D.;Portmann, Bernard C.;Ferrell, Linda D. (2006). MacSween's Pathology of the Liver (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 715. ISBN 978-0-443-10012-3.

- ↑ MG. 23 September 2009.