Difference between revisions of "Colorectal tumours"

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Colorectal tumours''', especially '''colorectal carcinomas''', are very common. They are the bread and butter of GI pathology. Non-tumour colon is dealt with in the ''[[colon]]'' article. | '''Colorectal tumours''', especially '''colorectal carcinomas''', are very common. They are the bread and butter of GI pathology. Non-tumour colon is dealt with in the ''[[colon]]'' article. | ||

''Colonic tumours'' and ''rectal tumours'' redirect here. | |||

An introduction to gastrointestinal pathology is in the ''[[gastrointestinal pathology]]'' article. The precursor lesion of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is, typically, an [[adenomatous polyps|adenomatous polyp]]. Polyps are discussed in the ''[[intestinal polyps]]'' article. | An introduction to gastrointestinal pathology is in the ''[[gastrointestinal pathology]]'' article. The precursor lesion of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is, typically, an [[adenomatous polyps|adenomatous polyp]]. Polyps are discussed in the ''[[intestinal polyps]]'' article. | ||

| Line 72: | Line 74: | ||

==Microsatellite instability cancers== | ==Microsatellite instability cancers== | ||

*Abbreviated ''MSI cancers''. | *Abbreviated ''MSI cancers''. | ||

{{Main|Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer}} | |||

=Specific entities= | |||

* | ==Colorectal adenocarcinoma== | ||

* | *[[AKA]] ''colorectal adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified''. | ||

*[[AKA]] ''colorectal carcinoma'', abbreviated ''CRC''. | |||

{{Main|Colorectal adenocarcinoma}} | |||

== | ==Secondary colorectal cancer== | ||

===General=== | |||

*Uncommon. | |||

*May be suspected. | |||

* | |||

* | |||

===Microscopic=== | ===Microscopic=== | ||

Features: | Features: | ||

*Normal colorectal mucosa. | |||

*Atypical cells in the lamina propria or submucosa. | |||

* | |||

* | |||

DDx: | |||

* | *Colorectal neuroendocrine tumour. | ||

= | ===Images=== | ||

== | <gallery> | ||

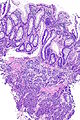

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum -- very low mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - very low mag. (WC) | |||

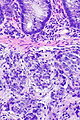

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum -- low mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - low mag. (WC) | |||

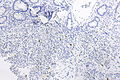

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum -- intermed mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - intermed. mag. (WC) | |||

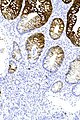

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum -- high mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - high mag. (WC) | |||

</gallery> | |||

<gallery> | |||

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum - PSAP -- intermed mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - PSAP - intermed. mag. (WC) | |||

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum - PSA -- intermed mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - PSA - intermed. mag. (WC) | |||

Image:Prostate carcinoma in rectum - CK20 -- intermed mag.jpg | Pca in rectum - CK20 - intermed. mag. (WC) | |||

</gallery> | |||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

| Line 178: | Line 113: | ||

*[[Gastrointestinal pathology]]. | *[[Gastrointestinal pathology]]. | ||

*[[Tumour budding]]. | *[[Tumour budding]]. | ||

*[[Tumour perforation in colorectal cancer]]. | |||

*[[Transanal minimally invasive surgery]]. | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

Latest revision as of 16:50, 29 August 2018

Colorectal tumours, especially colorectal carcinomas, are very common. They are the bread and butter of GI pathology. Non-tumour colon is dealt with in the colon article.

Colonic tumours and rectal tumours redirect here.

An introduction to gastrointestinal pathology is in the gastrointestinal pathology article. The precursor lesion of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is, typically, an adenomatous polyp. Polyps are discussed in the intestinal polyps article.

Classification

Most common

- Colon & rectum - most common = adenocarinoma.[1]

Others

Other tumours - many (incomplete list):[2]

- Mucinous carcinoma.

- Need > 50% mucinous component.[3]

- Adenosquamous carcinoma.

- Signet-ring carcinoma.

- Squamous carcinoma.

- Neuroendocrine neoplasms (carcinoid tumours).

- Lipoma.

- Leiomyoma.

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) - dealt with in a separate article.

- Angiosarcoma.

- Lymphoma (Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma).

Notes:

- Mucinous carcinoma - percentage required to call varies by site:

Squamous carcinoma

Main article: Squamous carcinoma

- Rare.

- In the context of a rectal tumour, retrograde growth from the anus should be considered.

Staging of colorectal cancer

Main article: Colorectal cancer staging

Pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma

Overview

Colorectal carcinoma is thought to arise from one of two pathways:[4][5]

- APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene mutation pathway, AKA classic adenoma-carcinoma pathway.

- Serrated pathway, AKA mutator pathway, mismatch repair pathway.

Syndromes

Both of the above described pathways are associated with syndromes:

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or familial polyposis coli (FPC).

- Lynch syndrome (AKA hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC)).

Pathways

APC gene mutation pathway

Microscopic:

Mismatch repair pathway

- Associated with microsatellite instability (MSI).

Other ancillary studies

- BRAF V600E missense mutation found in ~10% CRC.[6]

- KRAS mutation status.

BRAF V600E mutation

Main article: BRAF V600E mutation

Features:[6]

- Independently associated with BRAF V600E:

- Usually older (>70 years old).

- Female gender.

- Right-sided tumour location.

- Worse prognosis - in the context of metastatic disease.

KRAS mutation

Main article: KRAS mutation

- Patient must have wild type KRAS to get drugs; KRAS mutation predicts resistance to cetuximab (Erbitux) and panitumumab (Vectibix).

- Cetuximab and panitumumab are EGFR inhibitors.

Microsatellite instability cancers

- Abbreviated MSI cancers.

Main article: Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer

Specific entities

Colorectal adenocarcinoma

Main article: Colorectal adenocarcinoma

Secondary colorectal cancer

General

- Uncommon.

- May be suspected.

Microscopic

Features:

- Normal colorectal mucosa.

- Atypical cells in the lamina propria or submucosa.

DDx:

- Colorectal neuroendocrine tumour.

Images

See also

- Anus - covers anal cancer and anal intraepithelial neoplasia.

- Colon.

- Gastrointestinal pathology.

- Tumour budding.

- Tumour perforation in colorectal cancer.

- Transanal minimally invasive surgery.

References

- ↑ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 864. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ Humphrey, Peter A; Dehner, Louis P; Pfeifer, John D (2008). The Washington Manual of Surgical Pathology (1st ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 198. ISBN 978-0781765275.

- ↑ Tozawa E, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, et al. (2007). "Mucin expression, p53 overexpression, and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration of advanced colorectal carcinoma with mucus component: is mucinous carcinoma a distinct histological entity?". Pathol. Res. Pract. 203 (8): 567–74. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2007.04.013. PMID 17679024.

- ↑ Goldstein NS (January 2006). "Serrated pathway and APC (conventional)-type colorectal polyps: molecular-morphologic correlations, genetic pathways, and implications for classification". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 125 (1): 146–53. PMID 16483003.

- ↑ Rüschoff J, Aust D, Hartmann A (2007). "[Colorectal serrated adenoma: diagnostic criteria and clinical implications]" (in German). Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol 91: 119–25. PMID 18314605.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tie J, Gibbs P, Lipton L, et al. (July 2010). "Optimizing targeted therapeutic development: Analysis of a colorectal cancer patient population with the BRAF(V600E) mutation". Int J Cancer. doi:10.1002/ijc.25555. PMID 20635392.

- ↑ Dunn EF, Iida M, Myers RA, et al. (October 2010). "Dasatinib sensitizes KRAS mutant colorectal tumors to cetuximab". Oncogene. doi:10.1038/onc.2010.430. PMID 20956938.

- ↑ Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. (December 2008). "Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer". J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (35): 5705–12. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. PMID 19001320.